AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

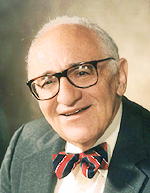

Murray N. Rothbard

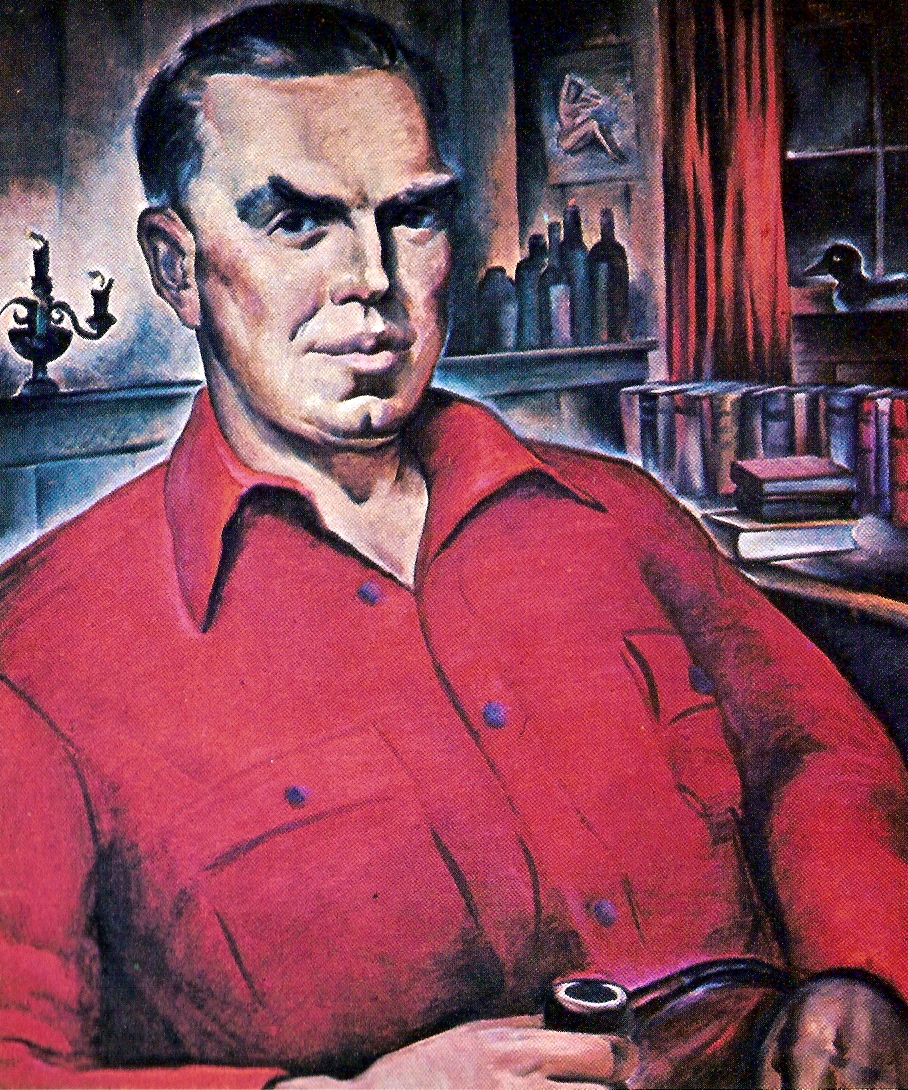

Harry Elmer Barnes

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

From Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought, IV, 1968, 3-8. This is Rothbard's editorial for what turned out to be that journal's last issue, which was devoted wholly to the last scholarly essay that Harry Elmer Barnes submitted for publication, "Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century," posted elsewhere on this site. Every issue of that journal may be read in facsimile on Mises.org, including this tribute by Rothbard.

Harry Elmer Barnes: R.I.P

Murray N. Rothbard

On August 25, 1968, less than a week after completing the final draft of the article which constitutes this issue of Left and Right, Harry Elmer Barnes died at the age of 79.

All persons leave an irreplaceable gap when they die; but this gap is truly enormous in the case of Harry Barnes, for in so many ways he was the Last of the Romans. He was the last, for example, of that stratum of rural Protestant boys who shed their religion at college and went on to constitute almost the entire founding generation of American scholars and university teachers. More specifically, he was the last of the founders of the “New History,” that movement at the turn of the century which, headed by Barnes’ friends and mentors Charles A. Beard, Carl L. Becker, and James Harvey Robinson, virtually founded the profession of historian in America and placed its entire stamp on historiography until the advent of World War II. And Harry Barnes was the last of the truly erudite historians. In a field of accelerating narrowness and specialization where the expert on France in the 1830’s is likely to know next to nothing about what happened to France in the 1840’s, Harry Barnes ranged over the entire field of historical study and vision. He was the Compleat Historian; and it was the historical approach that informed his work in all the other social science disciplines in which he was so remarkably productive: sociology, criminology, religion, economics, current affairs, and social thought. Surely his scholarly output was and will continue to remain unparalleled, as even a glance at a bibliography of his writings will show.

The quantity and scope of his productive output would alone stamp Harry Elmer Barnes as a memorable scholar, but this alone barely begins to scratch the surface of how remarkable a man he was. For he was that rarity among scholars, a passionately committed man. It was not enough for Harry to discover and set forth the truth; he must also work actively and whole-heartedly in the world on behalf of that truth. His was the opposite attitude from the detached irony of his friend Carl Becker. He believed, properly but increasingly alone, that it was the ultimate function of the vast and growing scholarly apparatus to bring about a better life for mankind; that the ultimate function of the scholarly disciplines is to aid in carving out an ethics for mankind and then to help put such ethics into practice. As devoted as he was to the discipline of history throughout his lifetime, he was just as devoted to putting its lessons to the service of man. Not for Barnes was the antiquarian “scholarship for scholarship’s sake”; for him the guiding star was scholarship for the sake of man. Hence the appropriateness of Carl Becker’s affectionate label for Barnes: “The Learned Crusader.”

It was Harry’s passionate commitment to truth that lost for him the applause of scholars and multitude alike and cast him, for the last two decades of his life, into outer darkness. During the 1930’s, Harry Barnes was acclaimed, by scholars and laymen, as one of the foremost intellectual leaders of his time. His books were reviewed, invariably favorably, on the coveted Page One of the New York Sunday Times Book Review. His column in the Scripps-Howard papers was read attentively by millions. But, in terms of continuing wordly eminence, Harry made one fatal mistake: he insisted, for ever and always, on being true to his convictions and to his principles, let the chips fall where they may. Hence, when liberal opinion, shortly before America’s entry into World War II, began to flip-flop en masse from its previous devotion to neutrality and non-intervention, and beat the drums for war. Harry Barnes, like his fellow liberals John T. Flynn and Charles A. Beard, stood steadfast. He refused to be stampeded by the interventionist war hysteria and he refused to keep his mouth shut over an issue so vital for mankind. He refused, like so many of his friends who knew better and had less to lose, to take the safer and more opportune course. He stood foursquare against the drive to war, and for his pains was summarily removed from his post as columnist by Roy Howard, who again knew better but felt that he had to bow to the intense pressure of interventionist advertisers against Harry Barnes. Like Beard and Flynn, Barnes found himself hounded by former friends and colleagues and denounced as a “Nazi” merely for cleaving to the liberal and pro-peace principles which all alike had shared a few short months before.

As America emerged from World War II as the world’s mightiest militarist and imperialist power, and prepared to launch the Cold War to maintain and expand that Empire, the Liberal Establishment, now vital in operating and apologizing for the Empire, would have been prepared to forgive and forget, as they did for many others. All Harry would have had to do was to keep quiet, to at least silently accept the New Order and the New America, and, above all, to refrain from taking the lead, as he had done after World War I, in revising the myths about the war and in calling the crimes of his own and allied governments to account at the bar of history and justice. Other historians, still “isolationist” about World War II, were willing to shut up and remain unpunished by the Establishment; but not Harry Elmer Barnes. Harry was a learned crusader; other men might grow more conservative and timid and accommodating to the powers-that-be as they grew older and more settled; but never Harry Elmer Barnes. That was to be his great burden during the remaining years of his life; but that was also to be his undying glory.

For two decades after World War II Liberal scholars and intellectuals led the way in the great “consensus” celebration of what America had become. But Harry Barnes could not participate in this jejune celebration. He reviled the militarism, the witch-hunts, the imperialism, the military-industrial economy, the “totalitarian liberalism” as he called it, that now characterized America, as well as the detached and Mandarin nature of the social science disciplines. He attacked all of these new trends, but he saw also that their roots lay in America’s entry into World War II, and that therefore a new general insight into the truths behind that war was vital if America were ever to throw off the shackles of its New Order.

And so Harry Barnes devoted much of the remainder of his life to creating a whole body of revisionist scholarship about the origins of World War II. As the Field Marshal of Revisionism after the first World War, Barnes had been in the company of the bulk of younger historians as well as the whole intellectual world, but now he was virtually alone, scorned by historians and laymen alike. But not for a moment did Harry allow himself to become discouraged or defeated. Single-handed, he virtually created a new revisionism. For every book and article revising the official myths about America and the Second World War, Harry Barnes was there in the forefront, discovering, inspiring, cajoling, admonishing, editing, promoting. He was the father and the catalyst for all of World War II Revisionism, as well as personally writing numerous articles, editing and writing for the Revisionist symposium Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, and launching the whole struggle immediately after the war with the first of numerous editions of his hard-hitting, privately-printed brochure, Struggle Against the Historical Blackout. Fortunately, Harry lived long enough to see the tide begin inexorably to turn among the historical profession, to see a New Left emerge that is beginning to call into question not only America’s current imperial wars but also World War II itself: especially in the work of William Appleman Williams and his students in modern American history. To his friends and colleagues the fact that Harry lived to see the emergence of his own vindication after so many years is the only slight consolation for suffering his loss.

Friendship: this brings us to Harry’s remarkable qualities as a teacher and as a friend. That Harry Barnes was one of the great teachers of his era is attested to by innumerable students, a large number loyal to the end despite fundamental disagreements on policies and points of view. His personal charm, his great generosity toward friends and students, as well as his own prodigious work and erudition. were able to inspire great loyalty and devotion among his students, and spur their own productive efforts. As a friend, Harry put all of us to shame with the quantity and quality of his letters; surely here was one of the most remarkable letter-writers of our time. Never could any of us write more than one letter for every three or four of Harry’s; and in them he would pour forth a seemingly endless stream of learned and candid comment, analysis, news, criticism, and generous praise. For Harry, friendship was never casual or superficial; it was devoted and deeply felt, and to it he gave as much concern and passion as he poured into his work as an historian or as a crusader. Inevitably, then, these friendships were often stormy; and I don’t believe there was any friend with whom Harry did not, at one time or other, break or almost break relations. But those who knew Harry only by reputation or in his uncompromising writings can never come to understand or savor Harry in person as he unfailingly was: cheery, courteous, a witty and often ribald raconteur, a marvelous and lovable companion. We shall miss him terribly.

Fortunately, Harry’s friends and colleagues have, for several years, been at work on a Festschrift, which has grown into a monumental testimonial volume describing and celebrating every aspect of Harry Barnes’ life and work. Forthcoming soon, it will be entitled Harry Elmer Barnes: The Learned Crusader, and it is the sorrow of all of us that Harry, while having read all of the manuscript, did not have the opportunity to see it in print. The book deserves the widest possible audience.

In the meanwhile, Left and Right is privileged to present what tragically turned out to be Harry Barnes’ last work, a work which he believed to be the final word on the task which had occupied him for the last quarter of a century: the true story of Pearl Harbor. Characteristically, Harry spent literally years adding to, revising, and checking the entire article, so that it would pass the highest and most rigorous standards. His friend, the Pearl Harbor expert Commander Charles C. Hiles, helped immeasurably in repeated reading and checking over the material. We have been delighted and honored that Harry chose the pages of Left and Right to present what he proposed to be his final word on the subject, the culminating synthesis of a quarter century of revisionist inquiry.

Some readers might ask: why? What’s the point? Isn’t this just a raking up of old coals? Aren’t we merely pursuing an antiquarian interest when we examine in such detail what happened over a quarter-century ago? The answer is that this subject, far from being antiquarian, is crucial to the understanding of where we are now and how we got that way. For America’s entry into World War II was the crucial act in expanding the United States from a republic into an Empire, and in spreading that Empire throughout the world, replacing the sagging British Empire in the process. Our entry into World War II was the crucial act in foisting a permanent militarization upon the economy and society, in bringing to the country a permanent garrison state, an overweening military-industrial complex, a permanent system of conscription. It was the crucial act in creating a Mixed Economy run by Big Government, a system of State-Monopoly-Capitalism run by the central government in collaboration with Big Business and Big Unionism. It was the crucial act in elevating Presidential power, particularly in foreign affairs, to the role of single most despotic person in the history of the world. And, finally, World War II is the last war-myth left, the myth that the Old Left clings to in pure desperation: the myth that here, at least, was a good war, here was a war in which America was in the right. World War II is the war thrown into our faces by the war-making Establishment, as it tries, in each war that we face, to wrap itself in the mantle of good and righteous World War II.

It is because of its enthusiasm for World War II and its leader, Franklin D. Roosevelt, that the Old Left has never been able to understand the straight and true line that leads from the New Deal and Franklin D. Roosevelt which they adore, to the Great Society and Lyndon Johnson which they despise. Lyndon B. Johnson is absolutely correct when he refers to FDR as his “Big Daddy.” The paternity is clear. It is this much-needed stripping away of the last remaining good-war and good-war-President myth that Harry Elmer Barnes accomplishes in his final article. It is a fitting note for Harry to leave us, for it is in a cause for which Harry fought and suffered all of his life: the cause of peace and justice and historical truth.