AnthonyFlood.com

Where one man sorts out his thoughts in public

From Ordered Anarchy: Jasay and His Surroundings, edited by Hardy bouillon, Centre for the New Europe, Belgim, and Hartmut Kliemt, Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, Germany. Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Hampshire England, 2007, Chapter 5, 59-92. I have placed each reference note near its referencing number (in smaller, blue font), rather than collecting them all at the end of the paper.

Anthony Flood

August 20, 2009

Concepts of Order

Frank van Dun

Dans toute l’histoire politique du monde, meme celie de l’Occident “chretien,” on a l’impression que, lorsqu’il s’agit de l’Etat, les triomphes de la justice sont presque des accidents, des anomalies.

R. L. Bruckberger1

1 In the whole of political world history, even that of the “Christian” Western World, one has the impression that as soon as the state is concerned, the triumphs of justice are little short of accidents, anomalies [my (i.e., van Dun’s) translation].

Unabashedly theoretic, Anthony de Jasay’s analysis of human interaction does not seek to create a technocratic framework within which rulers-managers (or their academic surrogates) can find handles for steering and manipulating the actions of other people towards some preferred optimal state of society. There is no trace in his work of the presumption that rulers and managers are, or can be, related to society in the same way that an engineer is related to a piece of machinery or an experimental biologist to the animals in his laboratory. Jasay’s bottom line is that rulers and managers are part of the real world of interacting agents that the theorist needs to analyse and understand. His arguments against the supposed necessity or desirability of the state derive much of their force from his refusal to compromise on that proposition.

If Jasay’s analysis of the problems of conflict and order among humans has not received the recognition that it deserves, the reason may be that the entire classical liberal tradition, to which it so clearly belongs, has been sidelined in contemporary debates and argu-mentation. To understand the pertinence of his argu-ments, one has to grasp the relevance of that tradition. That is no easy task for those—most of us—who have been educated by the state to look at the world as if it were inherently chaotic and in need of a firm government to protect it from self-destruction. Many liberals today construe liberalism as a scheme of organisation that can and must be imposed politically on society by an enlightened government, as if the arguments by which some intellectuals convince themselves of the superiority of the scheme would make every person oblivious to the opportunities offered by the mode of imposition itself. However, classical liberalism was not about imposing freedom but about safeguarding it. Its premise was that the human world has a natural law or natural order2 of its own, and that respecting personal freedom is crucial to that order. Consequently, the role of government, if it is to be lawful, must be restrained to maintaining respect for the natural law of the human world. Many authors in the classical liberal tradition accordingly devoted their intellectual efforts to specifying “constitutional restraints” that would keep the state within the bounds of law.

2 On the interpretation of “law” as order, see Frank van Dun, “The Lawful and the Legal,” Journal des econo-mistes et des etudes humaines, 6/4 (1996): 555-79.

Although Jasay eschews any notion of natural law that cannot be explicated in terms of his rational choice approach, he is fully committed to the view that there is indeed a natural order of the human world and that it will be attained most fully under conditions of lawful anarchy, that is to say in a regime of full freedom and unrestricted self-defence. Thus, he pushes the classical liberal argu-ment to a radical conclusion: assuming that “rational choice” covers political man as well as economic and indeed every other sort of man, there is no reason to expect that it is possible to confine the government of a state to its legitimate function. In a nutshell: granting the state the monopoly power to maintain the law is to grant it the power to abuse the law and, as Jasay famously asked, “What would you do if you were the state?”3 What would you do if you had the power to abuse the law without having to fear the one organization entrusted with protecting the law? What protection does a constitution offer against the state if the state is to be the guarantor of the constitution?

3 The first sentence of his The State (Oxford, 1985)

The purpose of this essay is to give a logical assess-ment of the classical liberal conception of law and order in the human world within an analytical framework defined by the general conditions or causes of conflict or disorder in human interactions. The first part (Interpersonal conflict), surveys the main positions on conflict and order in Western thought. Classical liberalism exemplifies one of those positions. Part 2 (Types of order), juxtaposes the relevant concepts of order and analyzes their constitutive relations. The analysis highlights the differences, discussed in the third part (Conflicting orders: liberalism and socialism), between the classical liberal concept of the “convivial order” or “natural law” of human affairs and the concept of “social order” that is central to all forms of philosophical socialism. “Rational choice” in the convivial order and in political society, the fourth and last part, concludes the essay with a short discussion of the application of “rational choice” analysis, in particular the prisoners’ dilemma model of interaction, to convivial and social orders.

Part 1: Interpersonal Conflict

Causes

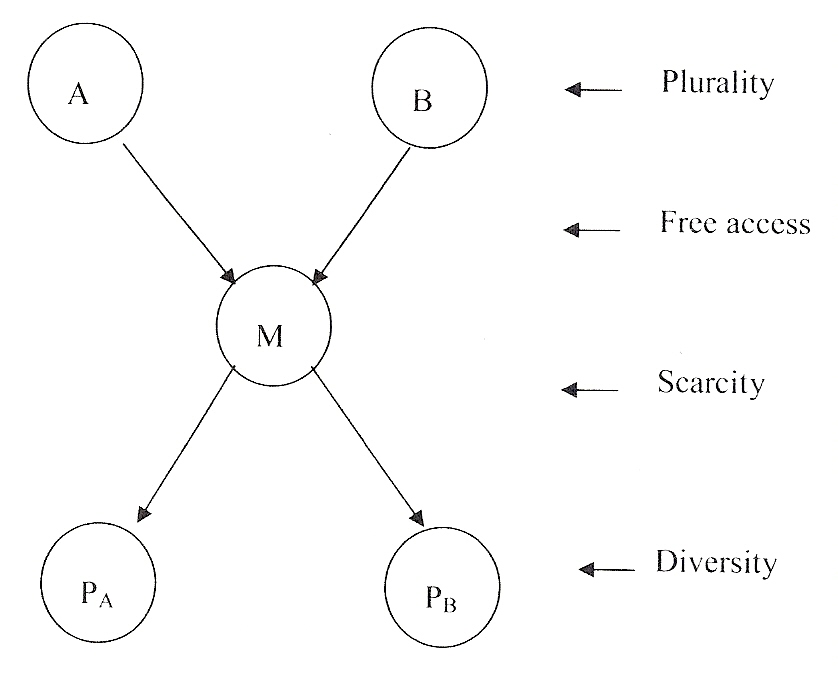

Let us consider the necessary and sufficient causes of interpersonal conflict as well as its possible cures. We shall begin our inquiry on a faraway island inhabited by only two persons, A and B. Because we are interested in interpersonal conflict, there have to be at least two persons. Evidently, this condition, which we shall refer to as “plurality,” is a necessary condition or cause of interpersonal conflict.

Obviously, plurality is not a sufficient condition. A and B must exhibit some diversity. They must have different opinions, values, expectations, preferences, purposes, or goals. If they were of one mind in all respects, in immediate agreement on all questions, there would be no possibility of conflict between them. Therefore, we should add diversity as a necessary cause of conflict.

Plurality and diversity do not constitute a sufficient set to explain significant conflicts other than mere differences of opinion. If plurality and diversity were the only conditions that mattered, A and B could easily agree to disagree and that would be the end of the matter. However, agreeing to disagree is no solution if A and B have access to some object M that is scarce in the sense that it can serve the purpose of either but not simul-taneously the purposes of both of them. If A succeeds in getting control of the object, then B must live at least temporarily with the frustration of not being able to get what he wants—and vice versa. There is at most one winner and at least one loser. Therefore, we must add scarcity and free access to scarce means to the list of causes.

Figure 5.1 Causes of conflict

We can visualize the situation on the faraway island in the conflict-diagram, which depicts the separately necessary and jointly sufficient causes of interpersonal conflict.

Cures

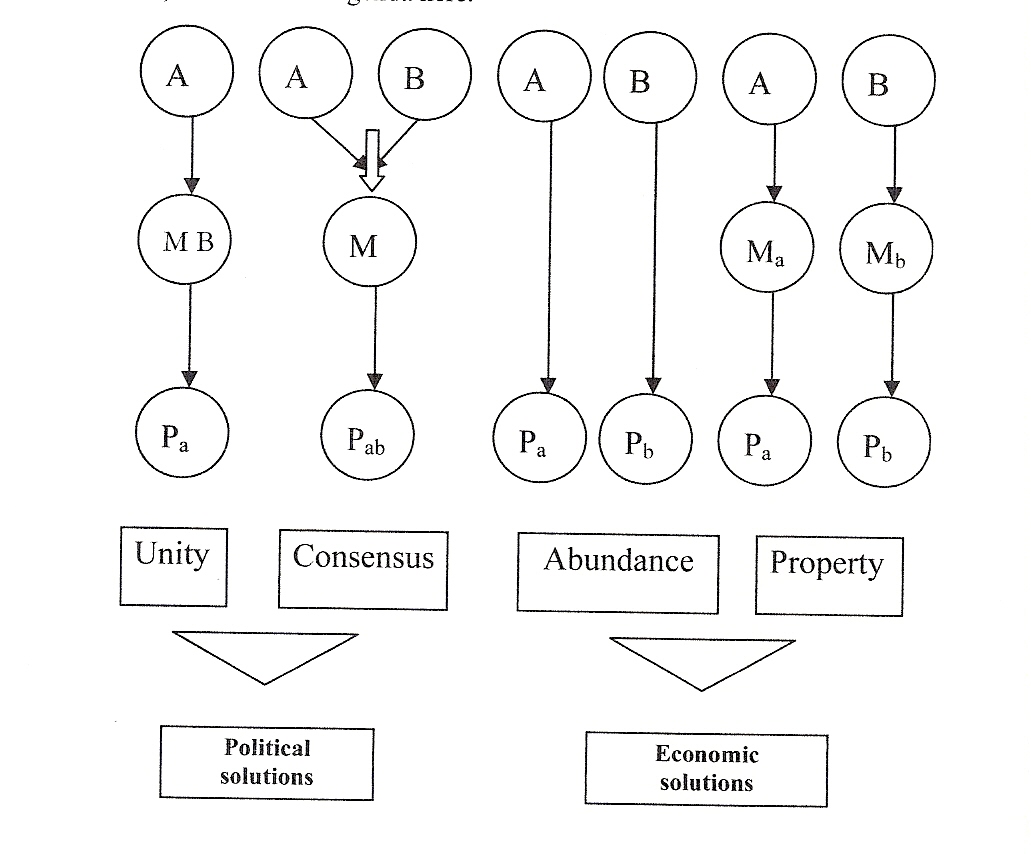

Given that each of the causes is necessary, it is sufficient to eliminate only one of them to eliminate the possibility of interpersonal conflict between A and B. Let us assume that we can tackle each of the four causes independently. Then there are four pure strategies for eliminating the possibility of interpersonal conflict. The first involves replacing plurality with its opposite, unity; the second replaces diversity with uniformity or consensus; the third eliminates scarcity and gets us into a condition of abundance; finally, the fourth introduces property, thereby getting rid of free access.

Confining ourselves to a “binary” classification that considers only two possible states for a cause (either it is present or it is not), we see that there are also eleven mixed strategies. Obviously, such a binary classification is not adequate if we want to study the “dynamics” of conflict and conflict-resolution, but for our analytic purpose it will do. Questions about weakening the causes to various degrees, about how much to invest in attempts to do that, about trade-offs between different solutions, and so on, are not on the agenda here.

Figure 5.2 Solutions of conflict

Unity involves the merger of A and B into a single person or else the reduction of a person (B) to the status of a mere means or an unconditionally loyal subject of the other (A). In any case, only one decision-maker or ruler remains. Consensus, on the other hand, requires that a set of opinions, valuations, preferences and the like is available in terms of which A and B can agree on the purpose for which and the manner in which M will be used.

As the graphical representation makes clear, Unity and Consensus involve the replacement of a plurality of independently chosen actions with one common, collective or social action. They imply a subordination of the actions of many to what has been called a “thick ethics,” one that stipulates not just how but also which ends are to be pursued. In particular, they subordinate “law” (which they typically interpret as legislation or authoritative commands and regulations) to some ruling opinion about what is good and useful. In the case of Unity, that is the ruler’s opinion. In the case of Consensus, it is an opinion shared by the people that matter. For this reason, we may label Unity and Consensus “political solutions.”

Note the contrast with Abundance and Property. Neither of these eliminates the plurality of independent actions. There is no single “thick ethics” that guides the actions of all concerned. Nevertheless, Abundance and Property are formulas of order. They subordinate any person’s ethics to the requirements of law, which defines the boundaries within which persons can seek to achieve their ends. Abundance and Property thus leave the plurality of persons and the diversity of their purposes intact. They only affect the scarce means. For that reason, we may label them “economic solutions” of the conflict-situation. Abundance is a condition in which it is possible for every person to do and get whatever he wants, regardless of what anybody else might do and therefore also without having to rely on anybody else’s co-operation or consent. Property requires only that each person can know which parts of the set of scarce means are his and which are another’s.

Each of the pure strategies has had its share of famous defenders in the history of Western philosophy. Plato4 and Hobbes5 immediately come to mind as strong advocates of unity. Despite the fact that we usually place them at the opposite poles of almost any dimension of philosophical thought and method, for both of them unity and only unity provides an adequate solution to the problem of interpersonal conflict. Like Plato’s philosopher-king, Hobbes’s Sovereign has the first and the last word on everything. Both argued forcefully that the slightest fissure in the structure of unity would lead to a breach of the political wall that protects the citizens from the ever-present threat of conflict and war.

4 In his last work, The Laws, Plato still defended unity, even if he appeared to have given up the hope that it ever might be realized: “The first and highest form of the state and of the government and of the law is that in which there prevails most widely the ancient saying, that ‘Friends have all things in common.’ Whether there is anywhere now, or will ever be, this communion of women and children and of property, in which the private and individual is altogether banished from life, and things which are by nature private, such as eyes and ears and hands, have become common, and in some way see and hear and act in common, and all men express praise and blame and feel joy and sorrow on the same occasions, and whatever laws there are unite the city to the utmost—whether all this is possible or not, I say that no man, acting upon any other principle, will ever constitute a state which will be truer or better or more exalted in virtue. Whether such a state is governed by Gods or sons of Gods, one, or more than one, happy are the men who, living after this manner, dwell there; and therefore to this we are to look for the pattern of the state, and to cling to this, and to seek with all our might for one which is like this” (The Laws, Book 5, 739c,d).

5 “For by Art is created that great Leviathan called a Common-wealth, or State (in latine Civitas), which is but an Artificiall Man; though of greater stature and strength than the Naturall, for whose protection and defence it was intended; and in which, the Soveraignty is an Artificiall Soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body” (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London, 1968), Introduction).

Aristotle based his political thought firmly on the re-quirement of consensus. As he put it, political society (and its first imperfect manifestation, the family) de-mands a consensus on what is good and useful.6

6 See T. A. Sinclair’s translation of Aristotle’s Politics (Book I, section 2), 1253a16-18: “[H]umans alone have perception of good and evil, right and wrong, just and unjust. And it is the sharing of a common view in these matters that makes a household or a city.”

What he meant, obviously, was not the sort of ad hoc consensus that we find in transactions on a market. The latter require no more than a contingent agreement on such small things as a particular good, its price and time of delivery. Nor did Aristotle mean a consensus on the conditions that make such transactions possible.7 [7 Aristotle, Politics (Book III, section 9), 1280a31-1281al.] While he agreed that justice in exchange is important, it was far from him to accept it as a respectable solution to the problem of conflict. What he had in mind was a sort of “deep consensus” to which the members of a political society8 could always appeal to resolve their initial disagreements—a consensus on fundamental values and opinions that marked the very identities of the persons involved in it.

8 At least its more notable members, those that fulfil the rather stringent conditions of citizenship that made them fit to rule. Among the inhabitants of a city that did not qualify as citizens Aristotle also counted the free men that were engaged in manual labor, trade and making tools. Their part in the political consensus of the city was minimal. It consisted in no more than acknowledging the right to rule of the best citizens.

Such a consensus could not take root except in the soil of shared experiences and longstanding affectionate and practical relationships.9

9 Although Aristotle made much of the fact that the polis was a “moral” rather than, like the family, a biological association, he insisted that it could not function well unless it was composed of family-groups that “occupy the same territory and can inter-marry” (Aristotle, Politics (Book III, section 9), 1280b35).

It required common history, tradition and custom to ensure that all the citizens would be educated to respect and esteem the same outlook on life in its theoretical, practical and above all moral aspects. Rousseau’s Du Contrat Social also exemplifies the consensus-solution. However, unlike Aristotle’s, his consensus could not be assumed to be historically given and transmitted almost as a matter of course from one generation to the next. It had to be created ex nihilo by skillful legislative and political manipulation on the basis of no more than a formal agreement to agree. It was, at least initially, an artificial construction of the sort that only an exceptional political genius, working on a “young, not yet corrupted people,” could hope to accomplish.

On a naive level of understanding, abundance merely involves a sort of equilibrium of supply and demand in the sense that resources are available in adequate quan-tities, so that everybody can satisfy his wants with ease and without detriment to anybody else. Before the technological and industrial revolutions of the nineteenth century, abundance was associated mainly with asceticism. Regardless of changes on the supply-side, there would be plenty for everybody if only people would reduce their desires (“demand”). Philosophies of asceticism stress control of desire and elimination of greed and covetousness. They look forward to a harmonious order of human affairs that should result from the adoption of a moral attitude of self-denial and contentment with a simple and natural life. The Cynics come to mind as proponents of this view, but we can give examples from more recent times as well (such as some of the more fundamentalist factions of today’s “Greens”). However, since the Enlightenment the idea of abundance rests primarily on the prospect of an enormous increase in the productive powers of mankind. Thus, abundance or liberation from wants and frustration now is identified with satisfaction of all desires, regardless of their number, quality or intensity. Many early nineteenth-century utopian socialists already fitted this description, but it was not until Marx had reinterpreted the old gnostic doctrine of total spiritual liberation in terms of material and social conditions that abundance came to mean the eradication of scarcity by the expansion of productive power.10

10 In The German Ideology, Part I, there is the famous statement that, under communism, “I can do what I want, while society takes care of general production.” That might mean that human life is split up in an autonomous spiritual part (the gnostic’s divine self?) and a material social part without any autonomy at all, which Engels described in his essay “On Authority” (1872). However, in his early manuscripts, Marx also hinted at true abundance with his vision of Man and Nature becoming truly One—the final realization of the gnostic’s dream of recapturing the original status of the true God, who knows himself to be All and therefore wants nothing. “This communism . . . is the genuine resolution of the conflict between man and nature and between man and man—the true resolution of the strife between existence and essence . . ., between freedom and necessity, between the individual and the species” (from the essay “Private Property and Communism” in Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe, vol. I, 3, 114-15, Moscow 1932).

Property rests on the idea that the physical, i.e., finite or bounded, nature of individual human beings, who are also rational agents and producers, is the primary fact that needs to be taken into account in any consideration of human affairs and relations. The objective or natural boundaries that separate one person from another also entail objective boundaries that separate one person’s words, actions and works from those of another. What lies within a person’s boundaries is his property. In so far as people respect each other’s property, there is order and justice; in so far as they do not respect it, there is disorder and injustice. Indeed, justice is respect for the natural order, i.e. the natural law, of the human world. Thus, justice requires human persons not only to respect other human persons but also their rights to the extent that these do not upset the natural law nor result from an infringement of it. For any person, these respectable rights are the accomplishments of which he is the author—the things that come into being under his authority, as his property. Being the rights of natural persons acting within their natural boundaries, they properly are called “natural rights.” In short, justice also requires restriction of access to any scarce resource to those who are by natural right entitled to it.

In Antiquity, the idea of Property apparently was taken up only by some of the Sophists. Unfortunately, with few exceptions, their thoughts are nearly inaccessible except through secondary and often hostile accounts. Their better known opponents, Plato and Aristotle in particular, were concerned primarily with the socio-political ordering of the city—with the positions, roles and functions that define its organization, and the selection of its officials. Thus, their city implied a radical division between insiders and outsiders as well as between the higher and lower orders of socio-political organization. They paid little or no attention to human affairs and relations among persons in so far as they were not defined in terms of social positions and functions. For them, the city was to a large extent the measure of the human person. In contrast, many of the Sophists apparently did develop a universalistic human perspective.11 [11 Eric Havelock, The Liberal Temper in Greek Politics (New Haven, 1957).] For them, the concrete, historical, particular, finite natural human beings are at any time and place the measure of all things, including the city. They saw cities and other conventional social organizations as no more than ripples or waves, continuously rising, falling, and disappearing, on the sea of human nature. As the sea rarely is without waves, so human history rarely is without social and political entities. However, just as no single wave is permanent and no wave is the fulfillment of the nature of the sea, no city or other socio-political organization is more than a transient phenomenon, shaped by a fleeting and contingent constellation of forces in human nature and its environment. Human beings may be sociable by nature, but they are not wedded by nature to any particular social order.12 12 Cf. their rational capacities may be natural but no particular language is the natural language of mankind.

Thus, for the Sophists, it was imperative to pierce “the corporate veil” of the city. They were interested in what people really did to one another, not in the conventional representation of their activities by political, social or cultural authorities. For them, law was “a surety to one another of justice,” and societies were “established for the prevention of mutual crime and for the sake of exchange.”13 [13 Aristotle, Politics (Book III, section 9), 1280b11 and 1280b30. ] Distant precursors of classical liberalism, they were not prepared to sacrifice the law of natural persons on the altar of any political organization, even one that was dedicated to the production of happiness and virtue.

It was not until the spread of the biblical religion that the idea of persons and their property acquired a fundamental significance in western civilization. That religion presented the world as essentially an interpersonal affair founded on mutual respect and covenant. It posited a relationship between a personal God (whom orthodox Christian doctrine eventually construed as a unified complex of three persons) and the human world (also an interpersonal complex involving many separate persons). According to its fundamental code, the Decalogue, the principal source of order in the relations between God and the world and in the relations among human beings is respect for the distinction between “thine” and “mine.” Politics had no part in this. While Jesus proclaimed that he had come to fulfill the Law (Matthew 5: 17), he repudiated the offer of “all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them” (4:8).14

14 “Il est impossible qu’il y ait entente absolument cordiale . . . entre l’ Etat et les chretiens . . . . [I]leur est même impossible de prendre l‘Etat et sa raison tout a fait au serieux.” [It is impossible that there is complete unanimity between the state and the Christians . . . . It is not even possible for them to take the state and its Raison completely seriously [my (i.e., van Dun’s) translation].] R.-L. Bruckberger O.P., L‘Histoire de Jésus-Christ (Paris, 1965), p. 177. Of course, Bruck-berger was not referring to twentieth-century European Christians, which he called “une collection de ballotins” (p. 176), a collection of empty paper boxes.

By the end of the seventeenth century, John Locke could give an account of order in human affairs that was entirely based on an appreciation of the human condition as an interpersonal complex, in which no person can claim any naturally given social position, rank or privilege. Understandably, a person’s property—the manifestation of his being, life or work in the natural order of the human world—was seen as his primary natural right, which reason could not but acknowledge as eminently respectable. “Property” took on its classical liberal guise.

Ranking Solutions

Which type of solution one prefers depends on one’s opinions about the feasibility and desirability of elimin-ating or attenuating one or another of the causes of conflict. Few people believe that it is possible to do much about scarcity, although, as noted before, there have been those for whom it is really no more than an illusion, the effect of a false consciousness. As for plurality, diversity and free access, many people appear to believe that they are far easier to manipulate than scarcity; however, they are also likelier to be considered values in their own right.

As we have seen, Abundance and Property tackle scarcity in different ways. Abundance refers to the elimination of scarcity in the fundamental sense of intrapersonal scarcity. That sort of scarcity refers to the fact that one can and therefore has to make choices. One cannot eat an apple and use it to make apple pie; therefore, one must choose what to do with it. Property leaves intrapersonal scarcity intact but removes free access and therefore interpersonal scarcity, which is the fact that one cannot have or use exactly the same thing that another person has or uses. Both sorts of scarcity imply the inevitable frustration of some wants, but only intrapersonal scarcity implies frustration for which one cannot blame another person. It depends solely on the variety of one’s goals and the limitations of one’s options. Even Robinson Crusoe, during the first lonely months on his island, had to face up to the intrapersonal scarcity of resources and to make choices about their most advantageous uses.

A person confronts intrapersonal scarcity when he becomes aware that whatever choice he makes has opportunity costs. Either he does a and gets whatever the consequences of doing a are, but then he cannot do b and therefore must forego its consequences; or else he does b at the cost of giving up whatever benefits doing a might produce. Choice and opportunity costs are inextricably linked.15

15 Only he that has no choices faces no costs. No matter what he does, it is the best because the only possible course of action. Hence the Stoics’ prescription for happiness: Renounce the illusion of freedom of choice, accept whatever happens as what is inevitably fated to happen, and so eliminate the risk of frustration and disillusionment. That, of course, is a classic ascetic version of the abundance-solution.

The cause of the inability to do a and b simultaneously may be in the nature of the person himself (his physical constitution) or in the nature of the external means at his disposal. The latter aspect—one cannot have one’s cake and eat it too—need no further comment. However, the physical constitution of the person is equally relevant. Human persons are finite beings, not only because they are mortal but also because at any moment their capacity for consumption is limited just as their productive capacity is limited. Consequently, a person, even one with infinite productive powers, or with immediate access to boundless supplies of consumption goods, would have to make economic choices. Unless he was completely indifferent with respect to all possible sequential orderings of enjoyments, he still would face the risk of getting much less out of life by choosing the wrong sequence of acts of consumption. Apparently, only a person with infinite capacities of consumption in an environment of superabundant consumption goods of every kind would be free from want and frustration.

Now, contemplate the co-existence of two or more persons, all of them with abundant material resources. From any person’s point of view, all others are external resources that can be put to many uses. Therefore, to the extent that one has desires and ideals that can be satisfied or realized only if others are or do what one requires of them, scarcity persists despite the abundance of other, non-human resources. True abundance, then, is a tall order. However, if it were possible, abundance would have nothing to fear from plurality, diversity or free access. The disappearance of intrapersonal scarcity takes the sting out of those other causes of conflict.

Compared to Abundance, the other solutions, Unity, Consensus, and Property, are less fantastic. However, they are not equal. Unity seems to be a more demanding condition than Consensus and the latter a more demanding condition than Property. Unity implies that diversity and free access have been eliminated as causes of conflict. The single remaining decision-maker has privileged access to all scarce resources and sets priorities for their use. Unity, however, may break down under the stress of scarcity. The decision-maker could make the wrong choices and thereby undermine his position, leaving him with too few resources to maintain his command amidst general dissatisfaction with his rule. On the other hand, if he could maintain unity, then, in a worst-case scenario, all of his subjects would perish with him if he made the wrong choices.

Consensus implies that scarce resources will not be accessed by anyone in a controversial way. In other words, it implies the elimination of free access. However, like Unity, it is vulnerable to the problem of scarcity. It could be a consensus on choices that are unsatisfactory in their effects and so provide incentives to defect to those people on whose consensus it relied. Alternatively, the consensus may hold but at the cost of collective disaster. Moreover, given that Consensus leaves plurality intact, it must invest in strategies that will ensure that the consensus does not become spurious. Thus, Consensus is always threatened by scarcity and by plurality.

Property, finally, only solves the problem of free access. Compared to Abundance, Unity, and Consensus, it is very nearly merely a technical matter. We may presume that most people will rise to the defence of their property as soon as they begin to understand how it can be taken away from them; and we may presume also that there is no iron law giving the advantage to the aggressors rather than the defenders. Thus, the property-solution appears to require no more than an adequate organization of self-defence. However, Proper-ty is vulnerable to the effects of scarcity, plurality and diversity, which it does not eliminate but merely accom-modates.

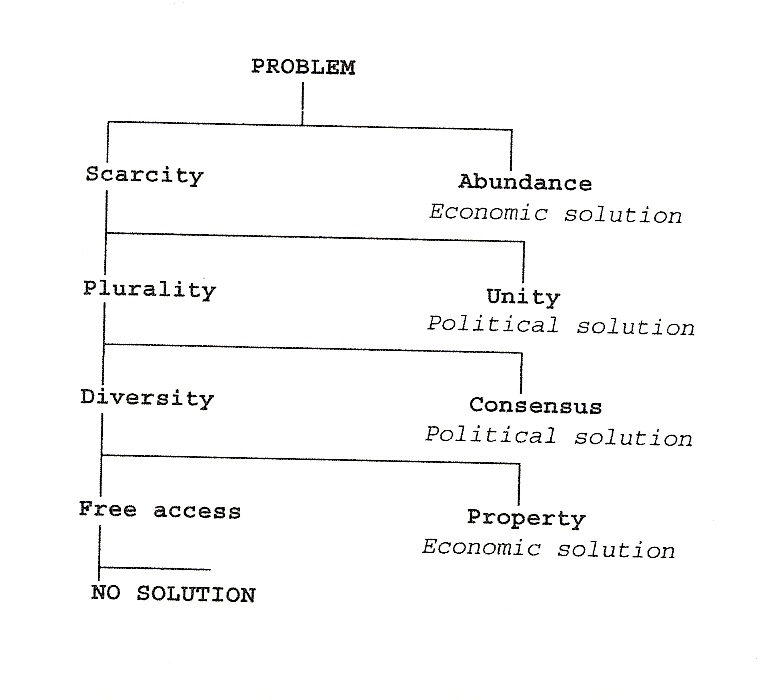

Because of such considerations, we can rank the different pure solutions on a single scale (see Figure 5.3). The ranking turns on the fact that a solution may imply the neutralization or elimination of more than one cause of conflict. Thus, Abundance requires the elimination of scarcity and implies the neutralization or elimination of all conditions under which Plurality, Diversity, and Free Access would give problems. If it were possible, it would also, for that very same reason, be the most complete solution to the problem of interpersonal conflict. With Property, the reverse is true. It requires elimination of free access but does not imply a reduction of plurality, diversity, or scarcity. Because it requires little tampering with the conditions of human existence, it is also the most vulnerable solution.

Figure 5.3 Ranking solutions

Utopianism

Abundance and Unity are more likely to be referred to as “utopian solutions” than either Consensus or Property. Marxian communism, with its prospect of a radical liberation from scarcity, fits the utopian idea very well. So does Plato’s idea of Unity.16

16 See the quotation from The Laws, Book 5, in note 4 above. Note, however, that in his better-known Republic (Book II, 369-75) Plato appears to argue that Unity should be restricted to the political sphere (the state) as the preferred way to eliminate uneconomic (violent, warlike) attempts to satisfy wants and desires. In other words, Unity is a way of sanitizing politics so that it will not interfere with the natural economic order of the supposed primordial “Golden Age.” In this interpre-tation, Plato should be seen as the first theoretician of the nineteenth-century’s political liberals’ ideal of a “constitutional state” with its radical separation of economics (“private law”) and politics (“public law”). Needless to say, nineteenth-century constitutionalism failed to heed Plato’s warning that the “guardians of the state” (civil and military servants) should be separated from the economic order of society not only physically, by being confined to barracks, but also psychologically, by being subjected to an educational regime aimed at eradicating every trace of personal interest or affection for anything not ordained by the state. Interestingly, Aristotle’s idea of a political constitution differs from Plato’s precisely by not envisaging a separation of political and economic power. Aristotle’s political citi-zens were the heads of the society’s economic units (households). This may be seen as a prefiguration of the modern corporate state, where the heads of significant interest groups (“corporations”) are the politically relevant (ruling, policy-making) citizens.

While Hobbes is rarely charged with utopianism, there nevertheless is a strong utopian undertone in his work. His definition of war as consisting “not in actuall fighting; but in the known disposition thereto, during all the time there is no assurance to the contrary,”17 [17 Hobbes, Part I, chapter 13.] leaves us with a definition of peace that is distinctly utopian.18

18 Leibniz noted this in his “Caesarinus Fürstenerius,” in Patrick Riley (ed.), Leibniz: Political Writings (Cambridge, 1988). Against “the sharp-witted Englishman,” Leibniz argued that “no people in civilized Europe is ruled by the laws that he proposed; wherefore, if we listen to Hobbes, there will be nothing in our land but out-and-out anarchy” (p. 118). According to Leibniz, Hobbes’s argument was a fallacy: “[H]e thinks things that can entail inconvenience should not be borne at all—which is foreign to the nature of human affairs . . . [E]xperience has shown that men usually hold to some middle road, so as not to commit everything to hazard by their obstinacy” (p. 119).

His Commonwealth—“a reall Unity of them all, in one and the same Person”19—[19 Hobbes, Part II, chapter 17.] is supposed to be the necessary condition of that utopian peace.20

20 Eric Voegelin, “The New Science of Politics,” in M. Henningsen, The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, vol. 5, Modernity without Restraint (Columbia and London, 2000), p. 218 also notes the gnostic-utopian theme in Hobbes’s argument.

If Consensus in its classical Aristotelian version cannot plausibly be charged with utopianism, the modern version, epitomized by the writings of Rousseau and other apologists for the sovereign republican State, does have a pronounced utopian streak. It derives from the idea that the republican state requires that human nature be changed.21 [21 J.-J. Rousseau, Du Contrat Social, Book II, chapter 7.]

The actual transformation of human beings into “true citizens” is necessary to produce a genuine political consensus without which the “general will” cannot but remain a lifeless legal fiction (and an easy target for the analytical attacks of rational choice theorists).

It was Plato who first adumbrated the theme of the transformation of human nature as a prerequisite of a just political order with his detailed description of the process by which natural human beings must be transformed into guardians of the city. Rousseau, an admirer of the Greek’s theory of political education, also shared his notion that among human beings the state cannot be justified. That idea, that human nature rules out a justification of the state, is the foundation of individualist anarchism,22 but Plato and Rousseau turned it into the proposition that to justify the state one should replace human nature with something that is by definition compatible with the state-“guardianship” or “citizen-ship.”

22 Referring to the theory of rational choice, Anthony de Jasay’s The State and Against Politics (London, 1997) offer many detailed arguments for that proposition. It has been a constant theme in the work of, among others, the late Murray N. Rothbard, e.g. The Ethics of Liberty (Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1982).

However, states did not begin to control formal education on a scale and with a determination approaching the requirements of Plato’s or Rousseau’s program until the twentieth century. Whether openly proclaiming their utopianism or disguising it as piecemeal social engineering, modern Western states embraced the notion of a “revolt against nature,” sweeping away much of Europe’s Christian and classical liberal heritage.

Arguably, Property is immune to the charge of utopianism. Neither the Sophists nor those in the modern Lockean tradition are prominent figures in the literature on utopian thought. Descriptions of what a liberal or libertarian world might be under ideal conditions fail to give an impression of utopianism. Even with the problem of free access solved and property as secure as it can be, people still are left to their own resources, or dependent on the charity of others, to make something of life. Indeed, those “ideal conditions” merely ensure that nobody has any guaranteed immunity from the slings and arrows of life. It is no wonder that Property gets short shrift in an age dominated by utopian hankering after guaranteed satisfaction of wants, except perhaps in the “ersatz” form of allegedly market-friendly government-imposed pro-growth policies—that is to say, as a means to approach the Abundance solution to the problem of order. Incisive and logically compelling as they are, Jasay’s arguments for the virtues of anarchy as a principle of order cannot but fail to strike a chord among those who have been indoctrinated with the notion that partisan politics—the art of externalizing costs—can be universalized into the art of eliminating costs.

Part 2: Types of Order

Social Order and Convivial Order

Unity and Consensus, as political solutions, require social organization: a social order or society, with a structure of command and obedience, and a hierarchical stratification of rulers and subjects, leaders and followers, directors and members or employees. Abundance and Property, on the other hand, as economic solutions, require no such thing as a society in that sense. The order they constitute is a convivial order,23 in which people live together regardless of their member-ship, status, position, role or function in any, let alone the same, society.

23 From the Latin convivere, to live together. I use “conviviality” primarily because its literal meaning is the same as that of the Dutch “samenleving” (literally, living together), which stands in contrast to “maat-schappij” (the Dutch word for society).

A society is an economy in the classical sense of “a household.” It is also a teleocracy (a system of rule aiming to achieve a particular set of ends, which may fixed by the society’s constitution, or left to the discretion of its leading organ). However, many societies have more or less extensive nomocratric24 sectors, which are defined by general rules of conduct rather than end-specific rules.

24 As far as I know Michael Oakeshott (Rationalism in Politics and Other Essavs (London, 1962) introduced the terms “teleocracy” and “nomocracy.”

For example, in modern politically defined or state-dominated societies of the Western type, “private law” (le droit privé, the regulation of the so-called private sector and the interactions of private citizens) often is nomocratic.

A family, a club, a ranch, a firm, a corporation, a church, a criminal gang, a state, or a state-like concoction such as the European Union—these are all examples of societies in the sense that is relevant here. At this point in the argument our interest is in the difference between the social and the convivial types of order per se; it is not in the manner in which order is achieved or maintained. Therefore, we need not consider here the obvious differences between, say, a criminal gang or a state, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, societies that pursue their economic, religious, cultural or recreational goals in peaceful ways, without resort to violence, coercion or fraud.

Because of their teleocratic structures and the unity of their planned collective actions, it makes sense to personify societies and to regard them as artificial or conventional persons defined by their constitution and social decision-rules. It does not make any more sense to personify a convivial order or to ascribe plans, opinions, values, decisions or actions to it, than it does to ascribe such things to its opposite, war. Thus, it makes sense to ask whether and how a particular society participates in the convivial order; but there is no sense in asking about the participation of the convivial order in a social order.

A convivial order is not a society. It is a catallaxy, an order of friendly exchange among independent per-sons.25

25 On the distinction between “economy” and “catal-laxy,” see F. A. Hayek, “The Confusion of Language in Political Thought”, in F. A. Hayek, New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and the History of Ideas (London and Henley, 1978), pp. 90-92.

We can find examples of convivial order in daily life, especially in the relations among friends and neighbors, among travelers and local people, and among buyers and sellers on open markets. We find them, in fact, wherever people meet and mingle and do business in their own name, whether or not they belong to the same or any social organization. There is no need for them to be aware of each other’s social affiliation or position, or of any teleocratic or nomocratic regulations that might be imposed by some society or other. Dealings between a natural and an artificial person (a society or one of its officials) or between two artificial persons may be said to be convivial by extension and analogy if they conform to the patterns (or laws) of friendly exchange among independent persons. However, the paradigm of conviviality is a relation between natural persons.

Although a convivial order is not a teleocracy and is an order maintained by adherence to general rules of conduct, it would be unwise to refer to it as a “nomocracy.” The latter term, like “autocracy,” “democracy,” and “aristocracy,” suggests a system of rule, government and administration, which does not apply to the convivial order.26

26 For this reason, Hayek (in Hayek, “The Confusion of Language in Political Thought”) preferred “nomarchy” to “nomocracy.”

A simple example of a nomocracy would be a soccer game. It is played according to a set of rules that apply equally to the competing teams and do not aim at a specific outcome of the game but nevertheless are eminently artificial and imposed legal rules. Similarly, a state-imposed nomocracy, for example in the form of “competition law,” is the implementation of a policy by the social authorities. Nomocracies are social constructs just as much as teleocracies are.27

27 Historically, the demise of teleocratic central planning in the last quarter of the twentieth century was not followed by the catallactic order of conviviality (the free market in the libertarian sense) but by more or less nomocratic forms of socialism (“the mixed economy,” “the third way,” “the active welfare state”).

In contrast, conviviality is an objective condition of interaction. Like its opposite or negation, which is war (disorder or confusion in, or a breakdown of, convivial relations), its presence or absence can be ascertained without reference to the rules of any organization, system of government or administration. Consequently—to use what once was a commonplace among lawyers—the laws of conviviality must be discovered; they need not be invented. From the point of view of political science, the convivial order is anarchical, maintained by a variable mixture of prudence, common decency, informal pressure, and (where not criminalized) investments in means of self-defence.

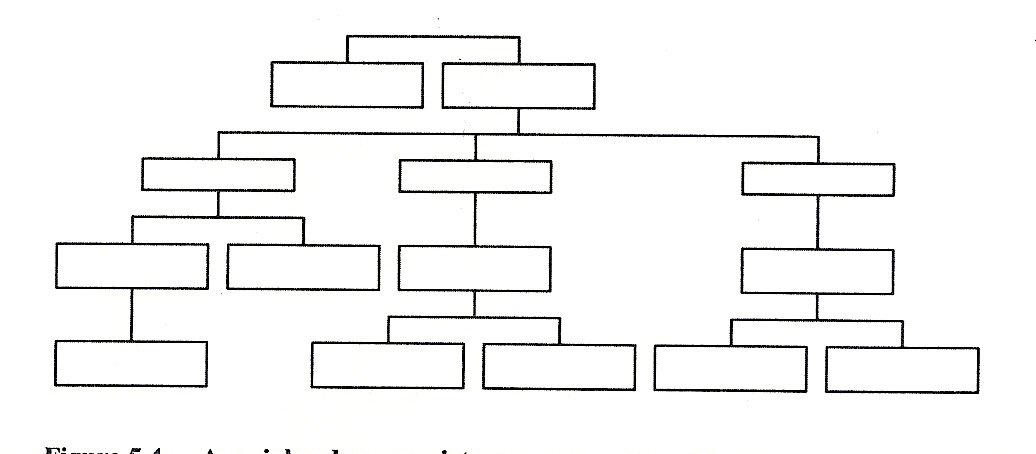

Figure 5.4 A social order or society

Significant Differences

To appreciate the differences between a social and a convivial order, we can draw a diagrammatic representa-tion of a social order (see Figure 5.4).

Students of legal systems, business administration, public administration, and social systems in general, are familiar with this type of organigram. From the family to the state, from the small entrepreneurial firm to the large corporation, the army or the church, every society can be represented by a more or less complex variation of the diagram. Indeed, a society is a system of social positions, each with its proper function, role, duties or entitlements—its proper “legal competence.”

A representation of the convivial order differs marked-ly from a social organigram. The figure gives us a snapshot of multifarious relations among many persons. Some of those relations are affective, others professional or commercial; some are fleeting, others durable; and so on and so forth. In the convivial order there is no formally fixed hierarchy of pre-defined positions, roles or functions. The fact that some people are more prominent or influential than others does not entail any difference in their status under the laws of conviviality.

Figure 5.5 The convivial order

Natural persons participate in a society as performers of one or more social functions or roles, as occupants of one or more social positions, each of which has a socially defined utility function attached to it. Moreover, as participants in a society they move in a world that is characterized by clearly defined positions, rewards, and punishments, and hence more or less fixed relations between actions and consequences. Thus, like the players of a game, they are inclined, indeed expected, to have a strictly utilitarian attitude towards decision-making. However, unless they are fully socialized, having internalized their “social identity,” there is no guarantee that they will abstain from seeking to use their position for purposes that are not part of, or may be at odds with, their social function. That is why societal organizers face the familiar problems of monitoring and controlling people to make them observe their “social responsibilities.” Apart from the societal organizers, the people in a society are no more than human resources, which—like other sorts of resources—have to be managed in the service of the goals set for the organization. In their endeavors to control the “human factor,” societal organizers may well try to eliminate it altogether, for example by training animals, or introducing machinery and computers. Where elimination is not possible they will resort to indoctrination or set up systems of incentives, rewards and punishments, or rigorous and easily monitored step-by-step procedures and ergonomic micro-management to provide motivation and to ensure efficiency. Human resources management is an integral part of social existence.

In a convivial order, in contrast, people appear only as themselves, doing whatever they do under their own personal responsibility. There is nothing like a social responsibility in the convivial order. No society takes the blame or appropriates the praise for any individual person’s acts and no person can get away with any kind of mischief merely by noting that he is only doing his job. While one person may agree to assume a larger or smaller part of the responsibilities and liabilities of another, every act remains someone’s responsibility.28

28 For a discussion of the implications of this for so-called “limited liability corporations,” see Frank van Dun, Personal Freedom versus Corporate Liberties (London, 2006, forthcoming). [Since 2009, available here.--A.F.]

In contrast, many societies have systems for passing on social responsibility that lead to nowhere, for example by placing ultimate responsibility with an inaccessible deity, an anonymous “public” or “people,” or an abstraction such as “society itself.” Such arrangements are inconceivable in a convivial order, where there is no corporate veil and responsibility is necessarily personal, not diluted by organization. Indeed, people may be held responsible—asked to justify themselves—by anybody, even a complete stranger, who is affected by their words or actions. Hence, to maintain themselves in the convivial order, people have to acquire an ethics of responsibility rather than an ability to prove that they are maximizing some “given” utility function.

Among other significant differences between a society and a convivial order, we note the conditions of mem-bership. A society necessarily has clear boundaries that separate its members from non-members because it is essentially an organization of men and resources that aims at some unique common goal or set of goals, which it tries to achieve by suitably co-ordinated collective or common action. To reach those goals, a society develops a strategy, assigns tasks and allocates resources to its officers and members.

All societies must work out the problem of securing enough income to pay for their expenses, and many face the additional problem of distributing a part or the whole of the social income among the society itself, its ruling members and its “rank and file.” A society does all of those things according to its customary, constitutional, statutory or legal rules, although contingency measures and the dictates of crisis management occasionally override their application. In any case, it must know who is a member of the society and who is not; what the members do and contribute and on what conditions they participate in social action. Formal and exclusive membership is a necessary condition of social existence.

A convivial order has no membership in that sense. It does not organize any collective or common action; it does not generate, let alone distribute, any social income. People can live convivially without being card-carrying members of the same club or association, without engaging in common pursuits or having a common leader, director, or governor. Whereas in a nomocracy such as a soccer game or a state’s private sector, people need some sort of certificate of registration or license to be permitted to play, they need no such thing in a convivial order. Conviviality requires no papers.

Elements of Order: Lex and Ius

Societies or social orders and convivial orders differ in their constitutive relations of order. Social orders essen-tially are lex-based or legal orders. The term “lex” refers to the Latin verb “legere” [to choose; to pick]. It denotes a relationship in which a person holds a position that entitles him to choose or pick others to do what he commands them to do. Its original meaning was the act of calling men to arms or to report for military duty.29

29 “Lex” is related to “dilectus,” (military) mobiliza-tion—confer the Roman “legions.”

Later, “lex” came to denote any general command issued by a politically organized society, one that is capable of enforcing obedience to its commands by military force. Eventually, the word acquired the meaning of a directive or rule of conduct that is generally accepted within a given society as being applicable and enforceable in some way by the social authorities, even if the society is not political. Calling a legal order “a social order” serves to highlight the fact that acceptance of and obedience to the legal rules is to a large extent a matter of habit or custom.30

30 “Societas” is related to “sequi” [to follow]: a society involves people who follow the same rules. In the representation of the solutions of the problem of interpersonal conflict, we see the lex-relation most clearly in the unity-solution, where A occupies the position of the legislator and B the position of the subject. In the consensus-solution, both A and B occupy the legislative position but only in so far as they are representatives of the consensus that supposedly defines the social order.

Thus, a social order implies the existence of a system of rules that define positions of “authority” or “command” to which other positions are subordinated. It is customary to personify such positions and to refer to them as to artificial persons, for example “ruler,” “legislator,” “director,” “rector,” “senate,” “general assembly,” “secretary,” “subject,” “employee,” “ser-vant,” “private citizen.” It is no more a matter of empirical science to determine what those social personages can or cannot do than it is an empirical question what the King, the Queen or a Knight in chess can or cannot do. To answer such questions, one should consult the appropriate legal texts or rulebooks, or people (legists) that possess expert knowledge of the applicable rules. Of course, one should take care to consult the right books and experts. A Queen in chess is not the same thing as a Queen in bridge; the rules defining the French Presidency do not define the American Presidency; and what a Belgian citizen can or cannot do may differ widely from the legal competence of an Austrian citizen. Every society, whatever its size, form or function, has its own legal system,31 which supplies the criteria for determining whether an act is legal or illegal.

31 Here we can see why legal positivists—for whom “law” denotes the legal system of a (state-dominated) society—must end up with empty-shell characterizations of “law,” such as Kelsen’s “dynamic system of norms that derive their validity from a single presupposed merely formal Grundnorm” [approximately foundational norm] and Hart’s “union of primary and secondary rules.” As for substance, “[positive] law can be anything,” ‘‘there is no logical connection between law and justice,” and so on.

Maintaining social order, therefore, is largely a matter of preventing or suppressing illegal activity, or else of changing the rules to legalize activities that, for one reason or another, are deemed acceptable by the current social authorities.

In contrast to social orders, the convivial order is ius-based. The word “ius” refers to the Latin verb “iurare,” which means to swear, to speak solemnly; to commit oneself toward others. The ius-relation implies no positions of authority or command, but direct personal contacts resulting in agreements, covenants and contracts, in mutual commitments, obligations or iura. Strictly speaking, the ius-relation can exist only between natural persons, as they are the only persons that are naturally capable of independent speech and action. It does not hold between a natural person and something that is not a person. In particular, it does not hold between social positions.32

32 By extension and analogy, it can be applied also to any two personified objects, such as mutually indepen-dent societies, provided that these are represented or operated by natural persons.

Unlike the lex-relation, the ius-relation holds between persons who need not be members or subjects of the same society. It holds between persons who are independent of one another, at least in the sense of not being related to one another as a superior to an inferior or as subjects of the same superior in any social organization.33

33 Referring to the types of order discussed in part I: the ius-relation most clearly finds a place in the property-solution. Neither A nor B having any say or authority over the other, any interaction between them must be justified in terms of their mutual respect, consent and contractual obligations. There is no other lawful way in which either of them could gain access to the means controlled by the other to reach ends that are beyond the powers embodied in his own means. Theoretically, we also could subsume the relations between A and B in the abundance-solution under the ius-relation, but there would be no point in doing so. Neither A nor B could gain anything from taking on obligations in a world without scarcity.

What natural persons can or cannot do is not defined by any set of legal rules. It is defined by their nature, which we have to accept as “a given” and to study accordingly. Moreover, we do not have to know any legal rules to determine which acts are injurious to natural persons or which acts are infringements of the order of conviviality among such persons. To make such determinations, we must study what really happened, what real people really did to one another, taking into account their mutual commitments and obligations—their iura. In short, we must study the world as jurists, not as legists, because the objective here is to determine whether an act was just (in accordance with ius), not whether it was legal or illegal in some society. Admittedly, iura can be as varied and diverse as legal systems are, but compared to the myriad of forms, sizes and functions of social entities human persons are remarkably similar beings.

The jurist as such is not concerned with legal rules but with rules of law. The latter, in the strict sense, are deductions from the conditions that constitute the convivial order of beings of the same natural kind. Thus, they are implied in the ius- or speech-relation itself, which requires the speakers to be “free and equal” in their exchanges of questions and answers, arguments and counter-arguments, proposals and counter-proposals, in order to communicate to one another what their commitments are. Obviously, physical intimidation and threats, lies and deliberately misleading utterances, and the like, defeat the purpose of entering into a speech-relation. One who engages in such things places himself outside the law because he willfully upsets the order of ius-based interaction by failing to deal with another as a free and equal person. In short, he is a criminal, one who does not respect the relevant distinctions (discrimina) that define conviviality.

In a wider sense, the concept of a rule of law also covers rules of justice, “technical determinations” of just and efficient ways to maintain or to restore the convivial order in a given historical context, where linguistic and other conventions enter into the understanding of human actions. One can easily recognize here the basic intuition of the theory of natural law—before it was derailed by attempts to derive the constitution of an ideal society from nature—that the fundamental patterns of order, the natural laws, of human relations are implicit in the rational nature of the physical human animal: its capacity of speech (ratio, logos) and its ability to act in accordance with such rationally undertaken commit-ments.

The study of “legal systems” and the “legal persons” they define is poles apart, with respect to its object as well as its methods, from the study of the ius-based convivial order among natural persons. The “law” (leges) of the legal positivists can be anything whatso-ever, but the jurists’ law, the ius-based order of convivi-ality, is in its principles the same always and everywhere. The same act may be legal in one society and illegal in another; but we need no legal reference to say that it is just, or unjust. Likewise for distributive justice: it primarily concerns a distribution of burdens or benefits according to principles on which the parties had agreed as a ius established among free and equal persons, regardless of any socially imposed rules. With respect to distributions within a social setting, “distributive justice” stands for a distribution based on an appreciation of merit (which necessarily must be relative to some task or purpose). In contrast, social justice—the satisfaction of every member’s wants by society, according to a socially defined ranking of either wants or membership status—is independent of agreement or merit. It brings to mind the Marxian illusion that we all can and are entitled to do and have what we want while society takes care of production.34

34 See note 10 above.

Conviviality, Natural Law, and Justice

From the above considerations, we can induce the basic structure of law.35

35 The argument and a detailed analysis can be found in “The Logic of Law.”

It is an interpersonal order that is ius-based. It com-prises at least two independent and autonomous36 persons.

36 On the technical meaning of “autonomy” in this context, see the text referenced in note 35.

Paradigmatically, they are natural persons, each of them exercising legislative power over his own property—the means of action, which may be material things or non-autonomous persons, that belong to him. If we assume the existence of only one autonomous person, the formal structure of law is reduced to a lex-based order. Simple as it is, the schematic representation of the ius-based interpersonal order has many interesting properties, but this is not the place for a detailed formal analysis.

From a philosophical point of view, the analysis is of interest primarily when we consider how human persons fit into the scheme, leaving aside all kinds of artificial and supernatural persons and piercing through the “corporate veil” of social constructions. At least at the moment of first contact, before either one has had a chance to do anything to the other, two natural persons can stand only in the ius-relation to one another. They are, at that moment, two independent (free) persons of the same natural kind, neither one being subordinated to the other. Of course, in this case, ex hypothesi, there can be no subordination in consequence of some pre-existing iura or of some previous injustice committed by one of them against the other. They are in a Lockean “state of nature,” which is the convivial order by another name. Their relation is according to the natural law. In terms of a once current definition of law, it is a relation characterized by freedom and equality.37

37 For my reservations about the use of “equality” in this context, see the paper cited in note 2.

Law is a condition of freedom among likes, that is rational agents of the same natural kind.

Justice, or ius-titia, is that which is instrumental for bringing about or maintaining the condition of ius. It comprises all actions that effectively aim at keeping human relations within the order of speech among free and equal persons. Thus, its main function is to prevent disorder or confusion from affecting the convivial order of natural persons. Injustice is first of all the result of not respecting another natural person as a free and equal person, for example by confusing him with something that is not a person at all but, say, a material object, animal, or a social construct. Other significant types of injustice result from confusing one natural person with another, especially when such confusion leads to rewarding or praising, punishing or blaming, one person for the words or actions of another. Such confusions, whether deliberate or not, whether rectifiable or not, betray an inability to abide by the conditions of conviviality.

Thus, with respect to the convivial order, “justice” has a clear and unambiguous objective meaning. Jasay rightly criticized the efforts of political and social theorists to appropriate the term “justice” while obfuscating its true meaning with various attempts to define justice as “something else.”38

38 Jasay, “Justice as something else,” which is the pivotal text in his beautiful collection of essays: Justice and Its Surroundings (Indianapolis, Ind., 2002).

Obviously, justice has no place in the legal-positivistic view that “law” is the legal system of one or another society. Maintaining social order or upholding the prevailing conditions of legality has no logical or other necessary connection with maintaining the ius-based order of conviviality. Who will deny that “There is no logical connection between lex and justice” sounds more plausible than “There is no logical connection between ius and justice?”

Part 3: Conflicting Orders: Liberalism and Socialism

The convivial order requires no social organization, only friendly, peaceful interpersonal relations. In that sense, it is a universal natural condition, the existence of which we can identify whenever and wherever there are contacts between people. In the same way we can identify its “negation,” which is war, or disorder or confusion in human affairs. Like that between life and death, the difference between convivial order and war comes, as it were, with the very nature of homo sapiens and his world. In contrast, societies are local, temporary and contingent constructions. There is no such thing as natural society. Nevertheless, awareness of the net advantages of co-operation and organization leads people to adopt a social mode of existence, to form or join one or more societies on the expectation that they will improve their quality of life or their chances of achieving cherished goals. This raises questions about the compatibility of social and convivial orders.

A convivial order conceivably may disappear when too many individuals start making war on one another, although it is difficult to see how such criminality could become infectious without being socially organized. As the word is used at present, war is pre-eminently a social phenomenon in that it involves high degrees of social organization and mobilization. Indeed, societies may be outlaws from the point of view of conviviality because of the way in which they treat their members or outsiders or both. Many societies thrive by perfecting the art of disturbing the conditions of conviviality by invasive actions of lesser or greater magnitude, from occasional raids to legalizing crimes or making lawful activity illegal39 to all-out war.

39 Prominent examples are the “underground economy” and other “victimless crimes.”

Although societies can be formed and operated on principles that are compatible with the convivial order, social orders are not necessarily compatible with the convivial order.40

40 “Society” is not the same as “community.” The latter term denotes a categorization of people with some common property or relation: locality, nationality, language, occupation, religion, and so on. Thus we have local, national, linguistic, religious, artistic, cultural, academic, criminal and many other communities. There is even a human community, a community of the living, and a community of the dead. Members of a society usually have a community of interests, but the community of people with a common interest need not be socially organized. Indeed, they may be only dimly aware of one another’s existence. Community leaders typically are strong personalities, not occupants of some predefined position—but many such leaders aspire to organize or “socialize” their community. A community has no “collective decision rules.” It need be no more than a segment or aspect of the convivial order. It is not a type of order distinct from either the convivial or the social order.

To some extent, all societies put the convivial order at risk. They imply some degree of hierarchical organization and mobilization—a concentration of power over men and resources that they can use for their particular social purposes. Moreover, societies tend to subvert the attitude of freedom among likes that characterizes conviviality. They offer rewards not just in the form of the accomplishment of their purpose or an occasional bonus or token of appreciation. They also offer differentiated social positions, which carry different sets of powers, privileges, immunities, perks of office, or financial benefits. Unlike the convivial order, where the concept does not even make sense, societies offer “career opportunities” and feed particular ambitions and rivalries regarding social position and rank. On the other hand, societies may languish, perish even, when they cannot adequately control the human factor. An atmosphere of either conviviality or war may pervade the social structure; the members may deal with one another as free and equal persons or alternatively as enemies. The social enterprise becomes pointless as the convivial attitude of live and let live or its warlike antithesis takes root to the detriment of social efficiency.

When there is incompatibility between social and convivial order, the question arises which type of order is more basic or worthy of respect than the other is. With regard to this question, classical liberals and philoso-phical socialists take radically opposed positions.

Philosophical socialists assert that social order trumps the natural law of freedom among likes. They focus on social orders, in which people occupy positions and perform roles and functions in the pursuit of some social goal. Consequently, efficiency in the pursuit of that goal trumps interpersonal justice, even if the goal is called “social justice.” For a socialist, human individuals are social resources or recipients of social benefits, in any case socially constructed “legal persons” with socially defined claims (“rights”) and duties. Hence, philosophical socialists face the task of socializing human beings to make them internalize the demands of society. In contrast, for a classical liberal, societies are human constructs, and human nature and natural conviviality trump social order. His task is to humanize societies to make them compatible with the natural law of conviviality. The main thrust of Jasay’s work is, that it is vain to expect the state to be of any help in that task. However, neither his nor anybody else’s critiques appear able to stop the relentless drive towards displacement of convivial modes of interaction by social forms that has characterized so much of recent history. If being reduced to a mere placeholder in a scheme of social organiza-tion—a resource to be managed—is the true mark of servitude then we are now very close to reaching the goal of what Aldous Huxley, not too long ago, called the “most important Manhattan Project of the future . . . vast government-sponsored enquiries into what the politicians and the participating scientists will call “the problem of happiness”—in other words, the problem of making people love their servitude.”41

41 Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (New York, 1953), p. xii (foreword).

Natural Law and Its Politically Motivated Denial

A person’s freedom under the natural law comprises any action that is compatible with the natural law of conviviality. It includes taking on obligations towards other persons and by implication entering into society with them provided the society in question is itself compatible with natural law. It does not include coercing others into submission either to him or to a society of which he is a member. It does not include coercing other persons who are in society with him, except to enforce in the agreed manner the rules according to which they had consented42 to behave and to act.

42 Obviously, “consent” does not refer to something outside the ius-relation. It refers to consent by a free rational agent, not to coerced or fraudulently obtained acceptance of conditions.

Nor does it include coercing others who are in society with him by taking anything from them that they had not agreed to invest in that society. In justice, withholding the benefits of membership is the only proper way in which to enforce social rules and regulations. The ultimate sanction is expulsion if that option has not been foreclosed at the constitutional level. Most societies can live with those limitations, but political societies, states in particular, obviously do not. Consequently, propo-nents of political social orders face the problem of justifying the very existence of political societies—the problem of debunking natural law.

Logically promising strategies for addressing that problem involve the rejection of freedom or equality, either of which is a necessary condition of natural law. Such rejections have been based on one of two arguments: one is that the condition (freedom or equality) is a true but undesirable and possibly dangerous state of affairs; the other is that the condition is no more than an illusion. Thus, Plato insisted that politics must resort to “a shameful lie.” All citizens must be taught that they are children of their country (and therefore brothers and sisters), but also that they are by divine ordinance destined individually for unequal social ranks.43

43 Plato, The Republic, Book 3, 413c-415c.

That indoctrination is necessary to ensure that they remain unaware of their natural condition and to make them accept social inequality. Similarly, Hobbes argued that equality was the root of all the evils of the “natural condition of mankind”44 and that only an absolute political inequality45 offered any hope of peaceful co-existence.

44 Hobbes, p. (part I, chapter 13).

45 Hobbes, p. (Part II, chapter 17).

Aristotle, on the other hand, went to great lengths to prove that social position is merely a reflection if not a fulfillment of natural endowment. The doctrine of “the slave by nature” was only the most telling illustration of his belief in natural inequality. For Aristotle, the freedom of the elite of noble citizens rested on their command over the lesser breeds of men. The natural inequality among human beings was his justifying ground of the socially necessary hierarchy and its division of human beings into free citizens and unfree subjects.

Until far into the eighteenth century, most attacks on natural law (in the sense of order among natural persons) were indeed attacks on equality. Later, the focus of the attacks shifted to freedom. Rousseau maintained that he could justify the fact that, although they are born free, people everywhere are in chains.46

46 Rousseau, Book 1, chapter 1.

Natural freedom is a fact, but it also is dangerous to human existence; that is why it should be replaced with civil liberty, which is obtained when every citizen becomes one with all the other citizens and therefore with the state. Civil liberty, then, requires the transformation of the human being from a natural, independent person into an artificial or “moral” person, the citizen. The latter is everything a natural human being is not. Above all, the citizen is only a part of a larger whole, and a part that is impotent without the assistance of the rest.47

47 Rousseau, Book 2, chapter 7.

A person’s natural freedom, his capacity for independent action and thought, must be eliminated if a state is to be legitimate and equality is to be instituted. Of course, that equality is no longer a qualitative sameness or likeness of natural kind, but a quantitative equality of rank and power in political society. Karl Marx went one giant step further by arguing that the particular individual’s freedom is an illusion—a reflection of his false consciousness. It will remain so until that individual is transformed into a true species-being and as a universal individual absorbs in himself the whole of humanity. Only then human society will become a universal society without differentiation of class or rank—a society of equals.

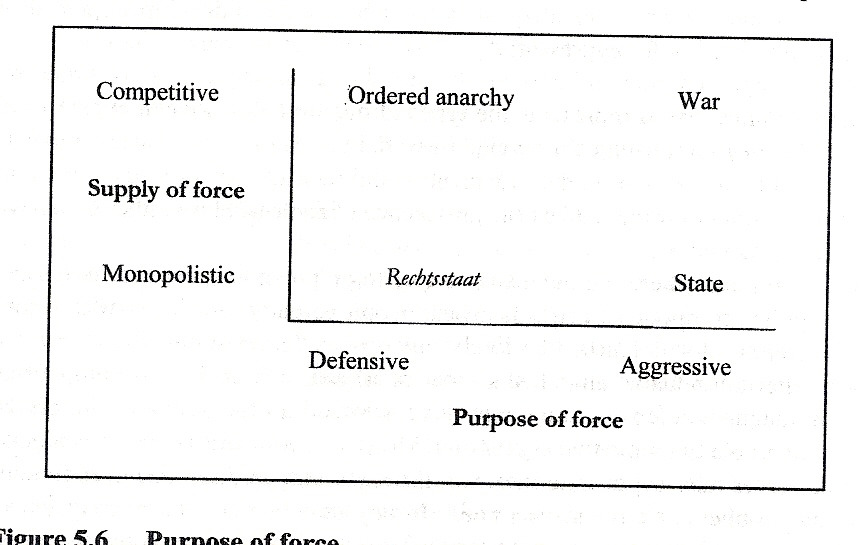

Figure 5.6 Purpose of Force

The vigorous currents of egalitarian and collectivist thought in the twentieth century and the strident rhetoric of “solidarity” indicate the enduring popularity of that mereological conception of the human person as an integral and dependent part of a larger whole.48

48 On the interpretation of those mereological ideas as reflecting a religious paradigm shift, see Frank van Dun, “Natural Law, Liberalism, and Christianity,” Journal of Libertarian Studies, 15/3(Summer 2001): pp. 1-36.

So does the conception of his liberty as equal participation in the “democratic self-determination” of that whole. It obviously does not bear any resemblance to a person’s freedom within the natural law. As far as a seemingly overwhelming majority of Western intellectuals is concerned, the idea of justice as freedom among likes holds no attraction at all. Despite Anthony de Jasay’s demonstrations of its vacuity, even many “liberals” cannot break free from the modern conception of liberty and equality as nomocratic legal constructs that must be democratically validated, regulated and enforced.

Ordered Anarchy Natural Order, the Problem of Adequate Defence

The peculiar problem of the natural law theorist is the vulnerability of the property-solution that we noted earlier. To put it differently, it is the problem of the adequate defence of every person against aggression and coercion—in particular against organized aggression and coercion, against aggressive and coercive societies. Statistically, in a man-to-man confrontation, the defender stands at least an equal chance against the attacker. Against an organized attack, he is nearly helpless unless he can organize an adequate force in defence of his property. However, it is in the nature of things that defensive force is reactive, organized to be effective against known threats. The initiative lies with the aggressors. Innovative aggressive techniques and organizations, against which no adequate defence has yet been developed, provide a window of opportunity for aggressors.49

49 Politically noteworthy examples are the invention of firearms and the organization of standing armies towards the end of the middle ages, and the development of powerful techniques of “rational administration” and of vast public bureaucracies and police forces in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

We can approach the problem of the instability of the convivial order by considering Figure 5.6. It represents the types of outcome that we can expect from different regimes concerning the availability of organized force. Each regime is characterized by a position on the organizational dimension (from monopolistic to competitive supply of force) and by the prevalence of force used for either defensive or aggressive purposes.

Under a regime where the defensive use of force prevails and where defensive force is supplied competitively (that is, where people actually can choose with whom they will contract for defence), the likely outcome is “ordered anarchy.”50