AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

From Phylon, Vol. 28, No. 3 (3rd Qtr., 1967), pp. 276-287. Anthologized in The Negro in Depression and War: Prelude to a Revolution, 1930-1945. Bernard Sternsher, ed. Chicago, 1969. See also his "Changing America and the Changing Image of Scottsboro" and his 2002 letter on Scottsboro elsewhere on this site.

The Study Guide for The Scottsboro Boys, the Broad-way musical that opened at New York's Lyceum The-ater on October 31, 2010, quotes twice from this paper.

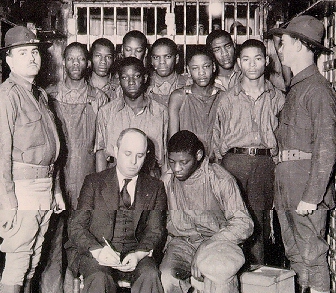

The NAACP versus the Communist Party: The Scottsboro Rape Cases, 1931-1932

Hugh Murray

In the South, conservatives are certain that communists are the instigators of the civil rights movement. American liberals hold that communists merely pose as advocates of civil rights in order that they may sabotage the aspirations of Negroes, thereby blackening the image of American democracy throughout the world. Diverse authorities can be cited in support of the liberal view. For example, both J. Edgar Hoover and W. E. B. DuBois could agree (at least, at one time) on communist perfidy in the Scottsboro rape cases.1 More recently, Langston Hughes wrote concerning the same cases in which nine young Negroes were accused of rape in Alabama:

. . . the NAACP’s initial efforts in behalf of the boys were nullified by the intervention of the Communists. The latter, seeking to exploit the matter for their own ideological purposes, misrepresented the NAACP . . . and persuaded the boys to abandon the NAACP-provided counsel, which included Clarence Darrow and Arthur Garfield Hays.2

Walter White judged that communist strategy in the Scottsboro cases was calculated to create “martyrs” of innocent Negro boys.3

Criticism of communist activities in the Scottsboro cases is numerous and varied. Some works of scholarship record that communists stole millions of dollars intended for the defense of the boys; others dwell on the incompetence of the communist attorneys, while a Jesuit scholar damns the Reds for betraying one of the Scottsboro boys, who had escaped, to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. This paper will be limited to a discussion of the most serious charge against the Communist Party—that it sought to sacrifice the young Negroes to martyrdom for the cause of communist propaganda.

In March, 1931, two white prostitutes were allegedly raped by nine blacks on a freight train near Scottsboro, Alabama. Feelings in the community were inflamed, and over a thousand National Guardsmen were needed to protect the boys (the eldest of whom was twenty years old) from lynching. For the trial, Judge A. E. Hawkins appointed the entire local bar to defend the youths, but before proceedings could begin a Chattanooga lawyer, Stephen Roddy, arrived. He informed the judge, “I am here . . . not as employed counsel for the defense, [but] people who are interested in them have spoken to me about it . . . .”4 After some discussion Roddy agreed to defend the lads with the aid of a Scottsboro barrister, Milo Moody. Eight of the boys were quickly found guilty, and all but the youngest were sentenced to die in the electric chair. It appeared as if most of the cases had ended on April 9, 1931.

Even before this date the International Labor Defense, a communist front organization, had shown interest in the cases. Its avowed purpose was to defend radicals and workers in the courts through two methods used in conjunction: first, the ILD endeavored to defend persons by the use of regular legal channels, e.g., by providing lawyers and appeals to higher courts; second, it sought to influence the courts with mass pressure by such means as demonstrations, petitions, and telegrams. Prior to these cases, ILD had been inactive in defense of Negroes.5 On April 2, the New York Daily Worker declared that “Alabama bosses” planned to lynch nine Negro “workers” in Scottsboro, and as the first trial opened in Alabama, communists had distributed anti-lynching leaflets. When the first verdicts were announced, the Party press decried them as frameups. The ILD telegraphed Judge Hawkins and other Alabama officials denouncing the trials and demanding the immediate release of the Negro boys. Should these ultimatums be ignored, the ILD warned, the recipients would be held personally responsible for the “legal lynching.”6

Judge Hawkins replied that such accusations were absurd. The Scottsboro boys “were given every opportunity to provide themselves with counsel,” he noted, “and I have appointed able members of the Jackson County bar to represent them. I personally will welcome any investigation of the trial.” Although Governor Miller of Alabama deigned not to recognize the telegrams, the attorney for the defense was less reticent. Stephen Roddy remarked, “I do not see how anyone can say that we were not striving to see that the defendants are getting the fairest trial.” On April 9, Roddy moved that the defendant Patterson receive a new trial, a motion that invoked an automatic stay of execution for the Negro. Roddy also contemplated similar actions for the other defendants.7

The ILD apparently attempted to lure Roddy and, with him, the defense of the Scottsboro boys to the Red banner, but Roddy rejected its appeal. Nor did he display any inclination of abandoning the cases to the communists. The ILD then tried to retain Clarence Darrow; he, too, declined the offer.8 Failing to secure either the attorney already managing the cases or the leading trial lawyer in the nation, the ILD employed George W. Chamlee of Chattanooga, a former Attorney General for the State of Tennessee.9

In addition to the legal defense, the ILD organized “mass action.” On April 12, some 1,300 workers demonstrated in Cleveland to protest the Scottsboro verdicts. The following day 20,000 persons attending a rally in New York adopted a resolution calling for the immediate release of the boys. Under ILD auspices other mass meetings were held in Philadelphia, Milwaukee, Omaha, Sioux City, Kansas City, Boston, Buffalo, Niagara Falls, New Haven, and Elizabeth, New Jersey. All echoed the same message—free the Scottsboro boys.10 Negro groups swamped the ILD and the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, another communist front, with requests for speakers on the Scottsboro cases. These speakers informed them that the boys were innocent, the girls were prostitutes, the courts were biased, and the defense had been inadequate.11 The organizations of Negro reform, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Urban League, and the Universal Negro Improvement Association, were chided on their silence by the communists.12 However, on April 24, a letter from William Pickens, field secretary of the NAACP, was reprinted on page one of the Daily Worker. Writing on the stationery of his organization, Pickens praised the efforts of the ILD in the Scottsboro affair. “This is one occasion for every Negro who has intelligence enough to read, to send aid to you [the Daily Worker] and to LL.D.”13 Finally, it appeared as if a united movement was gathering in support of the ILD and the Scottsboro defendants.

The same day that Pickens’ letter appeared in the Worker, the New York Times reported that the Scottsboro boys did not want communist help. The eight who were sentenced to die issued a statement to Stephen Roddy, two Negro ministers, and a former truant officer, all of Chattanooga. The youngsters, some of whom were illiterate, condemned the ILD and urged the communists “to lay off.”14 But the following day Mamie Williams, Ada Wright, and Claude Patterson, parents of three of the boys, solicited support for the ILD. They declared they had rejected the plea of some ministers that they repudiate the communists. Further, the parents reported that they had never been consulted about having Roddy represent their boys as defense counsel, and they denounced the ministers for sending Roddy to the Birmingham jail to entice their children into an attack upon the ILD. Some of the parents rushed to Birmingham to consult with their children, and one day after their first statement, all of the Scottsboro boys reversed themselves and paid tribute to the ILD.15

Communist hopes to monopolize the Scottsboro cases shattered, however, when on May 1, 1931, the NAACP announced that it had entered the cases and planned to manage the defense of the boys.16 Mutual denunciations by the ILD and the NAACP were precipitated by this unexpected statement of interest in the defense by the less radical Negro body. Both the NAACP and the ILD hoped to banish the other group from the cases as each organization coveted exclusive control of the defense. The NAACP had many advantages over its communist rival.

While the ILD was a novice in the field of Negro rights, the NAACP had twenty years experience. While the ILD was dominated by communists, the NAACP leadership was liberal and reformist. While the ILD demonstrated concern for the Scottsboro boys with telegrams and ultimatums, the NAACP had demonstrated greater concern earlier. This, at least, was the claim of the NAACP, and it was not to be dismissed lightly. The NAACP, since its inception in 1909, had fought many court battles under the banner of Negro rights. One pertinent instance was the Arkansas riot case (1926), which culminated in a United States Supreme Court ruling that a trial dominated by mob atmosphere is not a trial at all and is, therefore, a violation of due process of law. No Negro organization in America had the power, ability, and respectability of the NAACP. It was the accepted watchtower of Negro rights.

The NAACP maintained that it was the initial defender in the Scottsboro cases. According to Walter White, secretary of the organization, upon news of the arrests near Scottsboro, a number of Negro ministers in Chattanooga, along with the local chapter of the NAACP, stirred to action. Aware of the hostile feelings in Scottsboro, they feared that a Negro lawyer sent to defend the black youths would be ineffective, at best, in saving the lives of the defendants; at worst, ineffective in saving his own life. These Negro leaders asked a white attorney, Stephen Roddy, to represent them in Scottsboro. From this perspective, it was the ILD and not the NAACP that was interloping in the Scottsboro cases.17

There followed a scramble for signatures; both the ILD and the NAACP attempted to persuade the parents and sons that their respective organizations alone should govern the defense. Liberals supporting the NAACP soon charged that the ILD had hidden the parents of the Scottsboro youths to prevent the NAACP from presenting its views to them.18 Yet, The Crisis, organ of the Negro reform group, recorded in May, 1931, that one of its secretaries simply failed to convince the parents that they should engage the NAACP.19 Others of the “hidden” parents, Ada Wright, Josephine Powell, and Janie Patterson, were appearing at mass rallies in the East to gain support for their sons and the ILD. Some even attended NAACP convocations where the reform leaders denied them the privilege of speaking.20 The ILD asserted that the NAACP, failing to ensnare the parents, had attempted to influence the accused—minors, ignorant of many issues in the cases.21 The communists blamed the NAACP for the earlier visit of Roddy to the prison to “trap” the boys into signing a statement that they could not read and was not read to them.22

Fighting within the defense ranks continued. The City Interdenominational Ministers’ Alliance of Negro Divines of Chattanooga devoted its weekly broadcast to an assault upon the ILD “for its activities on behalf of eight Negro youths. . . .” The Alliance warned that communists posed a threat to the “peace and harmony” existing in the South. In addition, cautioned the ministers, the ILD’s objective was to win Negroes to the Red cause.23 Similar was the official NAACP analysis. According to its view, the aim of the ILD was to use the Scottsboro cases to spread revolutionary propaganda and to weaken and destroy the NAACP.24 It chastised the communists for being too narrow to see the superiority of the NAACP.

If the Communistic leadership in the United States had been broadminded and far-sighted, it would have acknowledged frankly that the honesty, earnestness and intelligence of the NAACP during twenty years of desperate struggle proved this organization under present circumstances to be the only one, and its methods the only methods available, to defend these boys.25

Although much of the energy of the communists was absorbed in portraying the innocence of the Scottsboro boys to the public, they could not ignore the charges directed against them by the NAACP and its allies. In rebuttal, the communists first reviewed the past. Either Stephen Roddy was or was not employed by the Chattanooga Ministers’ Alliance and the NAACP. The New Republic claimed that Roddy received $50.80 for his services, while Arthur Hays placed the figure at “about $100.”26 But in discourse with Judge Hawkins, Roddy denied that he was employed as counsel. The communists also questioned the quality of the services rendered by Roddy. Carol Weiss King, a civil rights attorney who assisted the ILD, described the defense as “half-hearted, or at least thoroughly incompetent.”27 At no time before the trials did Roddy interview his clients. He finally talked to them in the courtroom, immediately before the trials began. Although Roddy admitted he was unprepared for the task, he at no time asked for a postponement so that he might prepare. At none of the trials did he bother to summarize the case of the defendants.28 Finally, there was an at· tempt at compromise between Roddy and the prosecution that would have meant life imprisonment for the boys.29 In the eyes of the ILD, Roddy’s was no defense at all.

Thus, to the NAACP contention that it was the first and most effective defender of the Scottsboro boys, the ILD retorted that if the NAACP were first, it was horribly ineffective; and if it were not first, why was it intruding upon the ILD? If the Roddy defense were the best the NAACP could provide, it should surrender the cases to those who might do better. If the NAACP were not responsible for the Roddy defense, why did it claim to be? Could the communists, once they had entered the cases, withdraw in favor of an organization that claimed responsibility, rightly or wrongly, for a completely inadequate defense?30

Although only ILD counsel was present for hearings on May 6 and May 20, on June 5, 1931, Scottsboro became a mecca for various attorneys.31 Joseph R. Brodsky, ILD lawyer, obtained signed statements from the nine youths authorizing him and George Chamlee to act as their counsel.32 Roddy, who also appeared, announced he was happy “he did not represent any New York organization.”33 To this the NAACP made no comment. On June 23, the Jackson County Circuit Court denied the defense motion for a new trial and the attorneys for the boys filed notice of appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court.34

By early summer, 1931, the ILD, with the approval of the defendants, seemed to be in charge of the Scottsboro cases. But the NAACP was unwilling to capitulate, and it prepared a new offensive to gain control of the defense. In accord with changed NAACP policy, Walter White and William Pickens, organization secretaries, revealed that the Scottsboro youths had indeed been “railroaded” at their trials.35 This completely contradicted Roddy. Therefore, in appraising the past trials of the lads, the outlooks of the ILD and the NAACP converged. Notwithstanding the acceptance by the NAACP of the communist interpretation of the first trials, the NAACP was not planning to accept communist leadership in the Scottsboro cases.

The principal issue separating the two organizations was no longer the Roddy defense, but the role ascribed to mounting extra-legal activities. The ILD, like the NAACP, believed in providing a good defense in the courtroom; but the ILD believed more should be done. Rallies, demonstrations, and telegrams, or as the polemicists phrased it, “mass pressure,” were equally essential if the courts were to free the Scottsboro boys. Committees in the United States and abroad emerged devoted to the liberation of the Scottsboro youngsters. Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, Theodore Dreiser, Lion Feuchtwanger, Lincoln Steffens, John Dos Passos, and Suzanne LaFollette were all prominent in this effort.36 By July 7, 1931, Montgomery, Alabama, had received nearly 1,700 protests.37 Rallies and riots on behalf of the Scottsboro boys spread to Leipzig, Havana, the South, the world.38

The NAACP chose to do battle next with the ILD over the issue of mass action. “If the Communists want these lads murdered, then their antics of threatening judges and yelling for mass action. . . is calculated to insure this,” editorialized DuBois.39 The NAACP singled out a particular Red protest rally for special criticism. On July 17 at Camp Hill, Alabama, Negro sharecroppers met at a church to discuss the Scottsboro affair, but sheriffs’ guns closed the meeting. Some were killed, others wounded, and the church was burned. The NAACP viewed the incident as proof of the failure of communist tactics:

. . . black sharecroppers, half-starved and desperate, were organized . . . and then induced to meet and protest against Scottsboro. . . . If this was instigated by Communists, it is too despicable for words; not because the plight of the black peons does not shriek for remedy but because this is no time to bedevil a delicate situation by dragging a red herring across the trail of eight innocent children.40

However, while the NAACP aligned itself with the upholders of the law of Alabama in condemning communists (the Reds acknowledged instigating the rally) for causing the disturbance, the journal of the National Urban League and Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union placed blame on the Alabama officials who smashed the protest meeting.41

Despite the NAACP slurs on the communists and the ILD, it was George Chamlee of the ILD who, on August 7, filed a bill of exceptions in the Scottsboro cases; and it was he who asked for a change of venue to Birmingham in the case of the youngest defendant, who had to be retried because of a hung jury.42

The NAACP hoped next to stage a coup that would bring the prisoners back to their standard. On September 14, it announced that Clarence Darrow had been retained by the NAACP to defend the boys.43 Arthur Hays, attorney for the Civil Liberties Union, volunteered to serve the NAACP with Darrow.44 The day following their arrival in Birmingham, they were greeted with a telegram from the Scottsboro lads pleading with the famed counselors not “to fight the ILD and make trouble for Mr. Chamlee just to help the NAACP.”45 Instead, the boys begged them to join with Chamlee and the communists. A conference was arranged at which Darrow and Hays confronted Chamlee and ILD representatives. The latter offered to allow the entrance of Hays and Darrow on two conditions. “First, you must repudiate the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Secondly, the tactics in the case must be left to the International Labor Defense.” Darrow, opposed to ILD tactics, retorted with a counter proposal. All lawyers involved would repudiate their respective organizations and work as an independent force for the release of the Scottsboro youths.46 There could be little doubt as to which of these lawyers would dominate the independent coalition. To the ILD, mass pressure was essential to victory, while Darrow reasoned “it is idle to suppose that the State of Alabama can be awed by threats or that such demonstrations can have any effect, unless it is to injure the defendants.”47 Darrow had previously spurned the ILD’s offer to defend the Scottsboro youths; it now rejected him.48

Darrow then dropped the Scottsboro struggle, as did Hays.49 The NAACP, without support from parents, defendants, or lawyers, officially withdrew from the cases on January 4, 1932.50 The NAACP then characterized the ILD as opportunist, completely disinterested in the fate of the Scottsboro boys. The Reds rebuffed America’s leading lawyer merely for the sake of spreading propaganda through “mass action.” The ILD replied that Darrow was just the latest tool whereby the NAACP hoped quietly to sacrifice the defendants to “lynch courts.”51

The effects of the mass protest movement were indicated in Montgomery, when on January 21, 1932, Negroes and whites jammed the chamber of the highest court in Alabama and heard Chief Justice John C. Anderson announce that the jurists would not be “bulldozed.” He deemed the resolutions and letters that flooded the mails of the court highly improper.52 Not until March 24 did the State Supreme Court render its verdict, and in each of the cases Anderson alone dissented.53 The majority found nothing incorrect in the speedy trials and they viewed the National Guard as a bulwark against mob spirit.54 Anderson presented many reasons for his minority opinion: the trial occurred during the height of hostility against the boys a few days after the alleged crime; the presence of the military, which guarded the boys from the first night in Scottsboro and escorted them back and forth to Gadsden, was bound to have an effect upon the jury’s thinking; and the efforts of the defense were “rather pro forma than zealous and active.”55 Not for anyone of these reasons alone would Anderson order a new trial, but when considered conjointly, he discovered he could not uphold the verdicts of the Scottsboro juries.56

Nevertheless, the sentences were affirmed by a six to one vote. Only in the case of Eugene Williams did the outcome differ. Acknowledging that affidavits submitted by the defense to prove the youth yet a juvenile might be false, the court opined, “there is nothing in this case to prove their falsity.” Williams was remanded for a new trial, and the others were set to die on May 13, 1932.57

Although the ILD had succeeded in winning a new trial for one of the boys, the future for the other seven looked bleak. The New Republic lamented that without a violation of the federal Constitution, a murder case could not be appealed from the state to the federal courts. Because the cases concerned no question of constitutional law, the United States Supreme Court had refused to review the rulings on Sacco, Vanzetti, and Tom Mooney. Unless the ILD could demonstrate a violation of the Constitution, the Supreme Court would remain indifferent to the Scottsboro boys, also. Because of the similarity between the Scottsboro and the Arkansas riot cases, however, the New Republic held a faint hope of an appeal to the highest court.58

As the date of execution approached, public agitation intensified. The Berlin Committee for Saving the Scottsboro Victims wired President Hoover and Governor Miller of Alabama urging pardon for the Negroes. On April 7, a mob in Havana stoned the windows of an American bank, denounced Yankee imperialism, and demanded the freedom of the Scottsboro defendants. In response to foreign protests, the State Department in Washington asked Governor Miller for a statement of facts in the cases. American consulates abroad had requested the information in order to dispel the “misconception of the circumstances” in the cases.59

When the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the Scottsboro cases, the executions were suspended. On election eve, 1932, the tribunal’s decision on the cases was announced. Writing for the majority, Justice Sutherland chose to consider all of the cases as one. He observed that there were three contentions of the defense in support of its proposition that the defendants had been denied due process of law:

(1) they were not given a fair, impartial and deliberate trial; (2.) they were denied the right of counsel, with the accustomed incidents of consultation and opportunity of preparation for trial; and (3) they were tried before juries from which qualified members of their own race were systematically excluded. . . .

The only one of the assignments which we shall consider is the second, in respect of the denial of counsel; . . . .60

The Justice continued that at no time were the boys asked if they wanted counsel appointed. No one asked them if their parents or friends might hire attorneys. “That it would not have been an idle ceremony to give the defendants reasonable opportunity to obtain counsel is demonstrated by the fact that, very soon after conviction, able counsel appeared in their behalf.”61 Sutherland quoted from the court record where Roddy admitted that he was unprepared for the trial, unknown to the defendants, and unfamiliar with the procedure in Alabama. The appointment of the whole Scottsboro bar to defend the boys prior to the entrance of Roddy was designated as an “expansive gesture” on the part of Judge Hawkins; the appointment of the entire bar gave responsibility to so many that it gave it to none. Furthermore, Sutherland disclosed that one of the leading members of the bar had accepted employment on the side of the prosecution. Therefore, concluded the majority opinion, because the prisoners had been deprived of counsel in the significant pre-trial period, the period in which preparations for trial are made, the Scottsboro boys, even with lawyers at the moment of trial, were effectively deprived of counsel.62

In dissent Justice Butler proclaimed that the defendants had been adequately represented by counsel. He noted that if defense counsel had lacked time to prepare for the cases, it would have requested postponement. But this was not done.

There was no suggestion, at the trial or in the motion for a new trial which they made, that Mr. Roddy or Mr. Moody was denied such opportunity or that they were not in fact fully prepared. The amended motion for new trial, by counsel who succeeded them contains the first suggestion that defendants were denied counselor opportunity to prepare for trial. But neither Mr. Roddy nor Mr. Moody has given any support to this claim. Their silence requires a finding that the claim is ground for, if it had any merit, they would be found to support it.63

Butler complimented the original attorneys for their defense and remarked that no mob hysteria existed at Scottsboro. For these reasons Justices Butler and McReynolds upheld the convictions of the Scottsboro boys.

The majority ruling was, in the words of Felix Frankfurter, “the first application of the limitations of the [fourteenth] amendment to a state criminal trial.”64

The Scottsboro ruling, whatever its significance to the legal profession, was momentous to the ILD-NAACP dispute. The ILD appealed the cases on three grounds—mob atmosphere, denial of counsel, and exclusion of Negroes from the jury. Although one cannot state with certainty what the NAACP would have done had it governed the defense, one may speculate with a certain probability. The NAACP would have stressed the first point, attempting to demonstrate similarity between the Scottsboro and the Arkansas riot cases. This was the path suggested by Roddy, the New Republic, and, the day after the decision of the Supreme Court, by Walter White:

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People is elated at the Supreme Court’s decision granting a new trial in the Scottsboro cases. We are specially gratified that the decision reaffirms the principle and precedent established in a previous case, the Arkansas riot cases . . ., carried to the Supreme Court by this association, in which it was ruled that a court dominated by a mob is not due process of law.65

The high court did no such thing. Not only did Justices Butler and McReynolds deny that mob domination of the trials existed, but the majority also observed, “It does not sufficiently appear that the defendants were seriously threatened with, or that they were actually in danger of mob violence. . . .”66 An appeal based merely upon the town’s hostility to the defendants, then, probably would have failed in persuading the Supreme Court to overturn the convictions of the youngsters.

The third ground of appeal, regarding exclusion of Negroes from the juries, evoked no comment from the high tribunal. Therefore, if the NAACP had managed the defense and if it had appealed the cases employing this contention, it would be impossible to state the outcome in the Court. However, it is not impossible to ask if the NAACP would have made such a contention in appealing the cases. In its twenty-year history it had not done so. When the issue finally came before the Supreme Court, the ILD, not the NAACP, presented the arguments that ended, in theory, Negro exclusion from juries.

Only on the second point did the Supreme Court rule in favor of the Scottsboro boys, the claim that the youths had been denied effective counsel. It is doubtful, if the NAACP had supervised the cases, that the reform organization would have offered such an argument. For months the NAACP had claimed responsibility for the defense cited as inadequate by the Court—the NAACP had employed Roddy. Hardly could the Association have informed the Supreme Court that the counsel it had provided was the equivalent of denial of effective counsel. In fact, the position of the Court’s minority in upholding the Scottsboro verdicts was simply a paraphrase of earlier NAACP claims. The Communist Party stated, with justification, that not only had the ILD won a new trial, but that an NAACP defense would have resulted in the execution of the Scottsboro defendants.67

There were many more trials of the Scottsboro boys before an inconclusive denouement was to be achieved. Mass action in favor of the defendants continued, with songs, plays, poems, sports events, parades and a march on Washington devoted to their cause. It was the first time such widespread mass efforts had been staged on behalf of Negro rights, and the NAACP opposed them. Authorities criticize the communists for their mass campaign of the 1930’s, but the times and the Negroes are changing.

This paper began by noting the caricature of communists as held by many liberals and as reinforced by American scholarship. On closer inspection, allegations by DuBois, White, Hughes, Hoover, Nolan, Record, et al., that the Scottsboro case was an example of Red perfidy proves inaccurate—false. The communists did not attempt to make martyrs of the Scottsboro boys. Instead, through the ILD, the Communist Party saved the lads from a bungling defense and initiated a mass movement on behalf of the Negroes. Of course, there are other charges against the communists originating from their efforts in the Scottsboro cases—the ILD attorneys were incompetent, the Party stole millions intended for the defense of the boys, it betrayed one of the boys to the FBI after he had escaped from Alabama. Though these charges are as untenable as the one related in this article, lack of space precludes a detailed refutation.68

The Communist Party may or may not be villainous, but there is no evidence of its villainy in the Scottsboro cases. On the contrary, it saved the lives of nine young boys and opened new avenues of protest to Negroes.

Notes

1 J. Edgar Hoover, Masters of Deceit: A Study of Communism in America and How to Fight It (New York, 1958), p. 252; W. E. B. DuBois, Dusk at Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (New York, 1940), pp. 297-98. DuBois wrote this before his conversion to communism.

2 Langston Hughes, Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP (New York, 1962), p. 87. Hughes wrote this after he had praised the communists for their efforts on behalf of the Scottsboro boys many times in poems and plays.

3 Walter White, How Far the Promised Land? (New York, 1955), p. 215.

4 Arthur Garfield Hays, Trial by Prejudice (2nd ed., New York, 1935), p. 43.

5 James W. Ford and Anna Damon, “Scottsboro in the Light of Building the Negro People’s Front,” The Communist, X (September, 1937), 841; Wilson Record, The Negro and the Communist Party (Chapel Hill, 1951), p. 34; William A. Nolan, Communism Versus the Negro (Chicago, 1951), p. 75.

6 New York Daily Worker, April 2, 7, 1931; New York Times, April 9, 1931.

7 New York Times, April 9, 10, 1931.

8 Edmund Wilson, “The Freight-Car Case,” New Republic, LXVIII (August 26, 1931), 41; Walter White, “The Negro and the Communists,” Harper’s Magazine, CLXIV (December, 1931), 66; Hays, op. cit., p. 85; “A Statement by the N.A.A.C.P. on the Scottsboro Cases,” The Crisis, XXXIX (March, 1932), 82.

9 Wilson, op. cit., p. 41.

10 New York Daily Worker, April 13, 14, 15, 1931.

11 Ibid., April 21, 1931.

12 Ibid., April 22, 1931.

13 Ibid., April 24, 1931.

14 New York Times, April 24, 1931.

15 New York Daily Worker, April 25,1931.

16 Ibid., May 5, 1931.

17 White, op. cit., 64; “A Statement by the N.A.A.C.P. . . . ,” op. cit., 82; “Correspondence: The Scottsboro Rape Case,” New Republic, XLVII (June 24, 1931), 864. The latter contains a letter from Herbert J. Seligman, then Director of Publicity for the NAACP.

18 Wilson, op. cit., 42.

19 “A Statement by the N.A.A.C.P. . . . , op. cit., p. 82.

20 Files Crenshaw, Jr., and Kenneth A. Miller, Scottsboro: The Firebrand of Communism (Montgomery, Alabama: Press of the Brown Printing Company, 1936), p. 56. For a description of an ILD rally at which Mrs. Patterson appeared, see New York Times, April 26. 1931.

21 New York Daily Worker, June 29, July 6, 1931.

22 Wilson, op. cit., p. 42.

23 New York Times, May 24, 1931.

24 “A Statement by the N.A.A.C.P. . . . , op. cit., p. 82.

25 W. E. B. DuBois, “Postscript,” The Crisis, XXXVIII (September, 1931), 313.

26 Wilson, op. cit., p. 40; Hays, op. cit., p. 85.

27 Carol Weiss King, “Correspondence: The Scottsboro Case,” New Republic, LXVII (June 24, 1931), 155.

28 Ibid., pp. 155-56; King, “Correspondence: The Scottsboro Case,” The Nation, CXXXIII (July 1, 1931), 16.

29 Crenshaw and Miller, op. cit., p. 17; New York Daily Worker, November 16, 1931.

30 New York Daily Worker, May 5, 1931.

31 Ibid., May 23, 1931.

32 New York Times, June 6, 1931.

33 King, “Correspondence,” New Republic, op. cit., 155; King, “Correspondence,” The Nation, op. cit.,16.

34 Crenshaw and Miller, op. cit., p. 57.

35 New York Times, June 29, 1931.

36 Ibid., July 5, 1931; New York Daily Worker, May 20, 1931.

37 Crenshaw and Miller, op. cit., p, 57.

38 New York Times, July 1, 8, 12, 1931; New York Daily Worker, June 2, 1931. A German youth was killed in Chemnitz while protesting on behalf of the Scottsboro boys; see New York Daily Worker, December 14, 1932.

39 DuBois, “Postscript,” op. cit., p. 313.

40 40 Ibid., p. 314.

41 “Communism and the Negro Tenant Farmer,” Opportunity, IX (August. 1931), 36; New York Times, July 19, 1931.

42 New York Times, August 8, 1931.

43 Ibid., September 15. 1931.

44 “A Statement by the N.A.A.C.P. . . . ,” op. cit., p. 82.

45 As quoted in Hays, op. cit., p. 87.

46 Ibid., p. 88; Clarence Darrow, “Scottsboro,” The Crisis, XXXIX (March, 1932), 81; “A Statement by the N.A.A.C.P. .. . .” op. cit., p. 83.

47 Darrow, op. cit., p. 81.

48 New York Times, December 30, 1931.

49 Ibid.

50 50 Ibid., January 5, 1932.

51 Melvin P. Levy. “Correspondence: Scottsboro and the I.L.D . . . . New Republic, LXIX (January 20, 1932), 273; Robert Minor. “The Negro and His Judases,” The Communist, X (July 1931) 632 ff; James W. Ford and James S. Allen, The Negroes in a Soviet America (New York, 1935), p. 13.

52 Crenshaw and Miller, op. cit., p. 64.

53 Hays, op. cit., p. 92; New York Times, March 25, 1932.

54 Hays, op. cit., p. 92; New York Times, March 25. 1932.

55 Hays, op. cit., p. 98.

56 New York Times, March 25, 1932.

57 Ibid.

58 “Legal Murder in Alabama,” New Republic, LXX (April 6, 1932), 194.

59 New York Times, March 27, 31, April 9, 16, 1932.

60 Powell v. State of Alabama, 287 U.S. 50 (1932).

61 Ibid., p. 52.

62 Ibid., pp. 53-58.

63 Ibid., p. 76.

64 New York Times, November 13, 1932.

65 Ibid., November 8, 1932.

66 Powell v. State of Alabama, 287 U.S. 51 (1932).

67 New York Daily Worker, August 9, 1933.

68 Hugh Murray, Jr., “The Scottsboro Rape Case and the Communist Party” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Tulane University, 1963), p. 220 ff.

Posted March 14, 2007