AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

From Phylon, Vol. 38, No. 1 (1st Qtr., 1977), pp. 82-92. Elsewhere on this site are Murray's "The NAACP versus the Communist Party: The Scottsboro Rape Cases, 1931-1932" (cited in the 36th reference note below); his "Aspects of the Scottsboro Campaign"; and his 2002 letter on Scottsboro.

Changing America and the Changing Image of Scottsboro

Hugh Murray

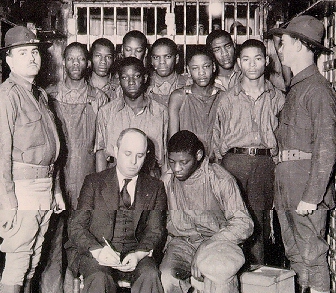

The Scottsboro rape case was not merely one of America’s most prominent causes célèbres, it was the most famous rape case of the century. To the dismay of American liberals the story of the nine young Negroes snatched from a freight train, nearly lynched, quickly convicted, and sentenced to death, was circulated round the globe in the 1930s by the international communist movement.1 From pam-phlets, petitions, and telegrams to protest rallies, parades, stoning of United States embassies, and the March on Washington of 1933, intense agitation was conducted on behalf of the Scottsboro boys. With a subject of such emotional interest—the alleged rape by young blacks of two white girls of questionable reputation in Alabama; the struggle between the liberal National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Communist International Labor Defense (ILD) to control the defense of the boys; the court room drama in which one of the white “victims” denied that she had been raped, and in which the prosecution appealed to anti-Negro, anti-Semetic, and anti-Northern prejudice; the secret negotiations and deals between liberal ministers and Alabama Governors—it would seem inevitable that the literature about Scottsboro be extensive. Nevertheless, a bitter complaint on this point was registered by Countee Cullen when he asserted, “Scottsboro Too, Is Worth Its Song (A poem to American poets).”2

However, if many poets did not sing of Scottsboro, others did, as well as others who may not have earned the title “poets.” The line between propaganda and literature is unclear, and if not all the works inspired by Scottsboro are of literary quality, they are of considerable quantity. Moreover, the content of the extensive literature of Scottsboro changed dramatically, reflecting the radicalism of the 1930s, the cold-war liberalism of the 1950s, and the vacillations of the late 1960s and early 70s.

One of the more prolific authors who wrote about Scottsboro was Langston Hughes, who had visited the boys in prison and had spoken on their behalf. In November, 1931, his one-act play “Scottsboro Limited” was published. A Communist interpretation of Southern conditions underlay the work, and the play ends with the raising of the Red flag while everyone sings the Internationale.3 Hughes also wrote poems dedicated to the plight of the nine accused: “Scottsboro,” “The Town of Scottsboro,” “Brown America in Jail,” and “Christ in Alabama.”4 But Hughes was not alone in finding Scottsboro a suitable text for literature. S. Ralph Harlow contributed a one-act play to the NAACP’s Crisis in October, 1933, focusing his attention on Judge James Horton who presided at one of the trials. “It Might Have Happened Somewhere in Alabama” opens on Good Friday, 1932, in the study of a judge. The jurist hears the radio describe the last days of Christ. He hears how Pilate tried to protect Jesus from the prejudiced mob and how the Roman governor hoped to evade sentencing the man before him. The judge begins to identify with Pilate, but demurs: “These illiterate nigger boys are not the Christ. Had I stood in Pilate’s place they could have torn me limb from limb. . . .” The harried judge opens his Bible to distract his attention, but he reads, “Inasmuch as ye did it unto the least of My brethren ye did it unto me.” After more soul-searching, his wife, calling him to dine, reminds him to wash his hands.5 There the play concludes.

Muriel Rukeyser had visited Decatur, Alabama, during one of the trials. Authorities arrested her for distributing leaflets, and Samuel Leibowitz, chief defense counsel, threatened to resign unless she and her comrades departed. Miss Rukeyser left Decatur, but not without impressions that she later composed in the poem, “The Trial.”6 Additional Scottsboro poems were written by Michael Quin, a “Duluth Worker,” Kay Boyle, and others.7

In March, 1934, a play written by John Wexley and produced by the Theatre Guild opened at the Royale Theatre near Broadway, The New York Times correspondent who had reported the Decatur trials of the Scottsboro boys, F. Raymond Daniell, was assigned the task of reviewing “They Shall Not Die.” He wrote of the production, “only one touch of realism is lacking. . . . That is the rich bouquet of perspiration and the acrid affluvia of stale tobacco juice.” He found everything so similar to the events he had witnessed that watching the play was like seeing a “dream walking.” He deemed the court scenes a carefully edited transcript and headlined his comments, “An Alabama Court in Forty-Fifth Street.”8 A similar review appeared in Opportunity in which Elmer Carter called the drama “realism, stark and unadorned.”9 The Communist New Masses analyzed some weaknesses in “They Shall Not Die.” First, the views of the ILD were insufficiently presented. Next, there was the emphasis on court-room atmosphere rather than the mass pressure aroused by the radical movements. Samuel Leibowitz, the bourgeois lawyer retained by the ILD, rather than the ILD itself, appeared as the savior of the boys. But the New Masses critic recognized the difficulty of exhibiting a radical drama to a non-revolutionary audience and concluded, “If one manages to undermine their faith in the capitalistic system, its morality, justice, esthetic, its other values, one is doing a great deal, one weakens resistance to revolutionary change. . . . Viewed in this light, They Shall Not Die is extremely successful.”10 As expected, the NAACP’s Crisis reviewer was less enthusiastic about Wexley’s play. He called it “propaganda for the Communist party transferred to the stage” and was especially critical of the parts disparaging the NAACP. After the first act, however, the reviewer noted improvement and was gratified when the audience hissed the prosecutor and cheered the boys’ defense attorney.11 Another Scottsboro play had the misfortune to open within a week of the Wexley drama, and “Legal Murder” by Dennis Donoghue, soon closed.12

In 1934 Thomas Stribling completed a trilogy of Southern life with Unfinished Cathedral. This novel begins with an attempted lynching of young Negroes accused of raping a white girl on a freight train. But as the story progressed, the rape case grew ever more peripheral. Instead, Stribling stressed issues echoing the 1920s—evolution, a girl’s chastity and her high school beau, the generation gap, a real-estate boom and bust, church membership for an unbeliever, and a Civil War battle reenactment. These questions displaced the issues of alleged rape and race.13

In addition to the plays, poetry, and part of a novel derived from the Scottsboro case, the cause célèbre exerted its influence in. other fields. The Daily Worker printed a song with music and lyrics, “The Scottsboro Boys Shall Not Die.”14 Moreover, there were Scottsboro ballads, a Scottsboro dance, and “The Death House Blues.”15

Should the definition of visual art include cartoons, then dozens of sketches based on Scottsboro in the Communist press and elsewhere would be relevant. Pictures were also relevant in another way—film star James Cagney served as an auctioneer at an art sale in San Francisco to raise funds for the Scottsboro defense.16

In the mid-1930s there were new developments in the Scottsboro case. The Communist Party lost its paramount role in conducting the defense of the boys, and a coalition was forged with the formation of the Scottsboro Defense Committee (SDC). A popular-front organization, it had the support of the Communists though its leadership was liberal. A new phase of the Scottsboro case began. Behind closed doors liberal ministers and racist Governors debated the fate of black youngsters unjustly imprisoned. In 1937 the State of Alabama compromised, allowing four of the nine boys to go free. In return, the SDC promised that Communists would not agitate about Scottsboro. The Communists agreed, and such agitation, propaganda, and literature virtually disappeared.17 During World War II most of the other boys were quietly released on probation. One, the most radical, was not. On July 21, 1948, Haywood Patterson escaped after seventeen years in Alabama prisons. The anti-Communist chairman of the SDC, the Reverend Allan Knight Chalmers, advised the thirty-five-year-old Negro:

Choose a new name. Don’t tell me what you call yourself or where you are. Begin to live a new personality. Don’t think of yourself as a Scottsboro boy. Whenever the word Scottsboro is mentioned, don’t let the expression on your face change. Don’t seem to have any feelings about it.18

Patterson, the militant who rebelled in prison when mailing and visiting rights were denied him, the activist who chose to free himself rather than wait an undetermined time for the SDC to persuade the Governor of Alabama to release him, chose not to forget. Patterson renewed his contacts with the radical ILD, which had since merged with the National Negro Congress to form the Civil Rights Congress (CRC). Patterson recalled his experiences to Earl Conrad. Just as the last Scottsboro defendant remaining in jail, Andy Wright, won his second parole, Scottsboro Boy appeared.19 Published by Doubleday, Patterson’s biography was not intended as a definitive history of the Scottsboro case, but as a “revelation of the actual day to day life of Negro men in prison camps of the deep South.”20 A reviewer in the Journal of Negro History wrote, “Other works have treated this general subject, but few, if any, have described their personal experiences so intimately and with such thorough going detail.”21 Abner Berry, in another review, titled his piece “American Dachau.”22 On June 27, 1950, the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested Haywood Patterson in Detroit, and Alabama requested his extradition.23 Governor G. Mennen Williams of Michigan refused to return Patterson to the South, and Alabama authorities chose not to prosecute the Negro in a Michigan court.24 All the Scottsboro men were then free.

As the post-war years became the cold-war years Scottsboro became for American society an incident to be forgotten, a memory to be repressed. In 1949, when “They Shall Not Die” was restaged in New York, anti-Communist thugs assaulted the actors.25 In 1950 when the Governor of Alabama failed to win Patterson’s extradition, he called the case a closed book. Except for a rare news article or a brief reference by a state or national committee investigating alleged subversion, the Scottsboro case and its defendants faded into the obscurity of personal problems and scholarly distortion.26 Then in 1955 the Scottsboro tale was resurrected indirectly in Don Mankiewicz’s successful novel Trial, which won a Harper prize and was made into a film. Trial was neither a history of Scottsboro nor an historical novel based directly on the case. Yet so many events in the Alabama incident paralleled those of the Mankiewicz novel that the book must be considered a thinly veiled and extremely partisan view of the Scottsboro case. Trial was set in California. Marie Wiltse, a white girl with a history of heart disease, is approached by Angel Chavez, a young man of Mexican descent. They kiss; his hands wander. The girl becomes frightened, she screams, and the boy attempts to quiet her. In the struggle the girl dies of a heart attack, and the youth is charged with murder. A lawyer for the Mexican Advancement Association plans to defend the boy, but he yields the case to Bernard Castle, who shares the defense with his new associate and the protagonist of the novel, David Blake. Castle is to raise money for the defense while Blake manages the legal phase of the case.

Tempers flare in the California town because of the death of Marie Wiltse. Racists nearly convert her burial into a lynching party. Meanwhile, Castle induces the defendant’s mother to accompany him to New York to raise funds. After a few weeks, he calls Blake to the East to aid the money-raising effort. In a New York taxi taking him to the Arena, Blake related to the driver that he is going to attend a rally. The chauffeur responds, “Ah read about that rally. . . . Some Nigger raped a white gal, and a bunch of yids are trying to get him off.”27

Blake discovers he is working with Communists, who are diverting funds from the Chavez defense to other radical efforts. Dejected, he returns to California to try to save Angel in court. Blake’s attempt appears successful as the trial nears a close, but then Castle demands that Blake place the defendant on the witness stand. Blake opposes the move at first, but he yields. The lad testifies and becomes confused under cross-examination. Chavez is found guilty and is electrocuted. At the climax of the story Castle’s disillusioned secretary confesses to Blake that Castle is a Communist, that he snatched the case from the MAA attorney through blackmail, and that it was he who told the racist lynchers where the family burial of Marie would occur. Finally, it was Castle who insisted that Chavez testify, because the attorney wanted the jury to convict the young Mexican. Why?

Because Barney’s new world’s acoming. A world where a man’s color won’t make any difference. A world—oh, hell, you’ve heard about it. And to bring that world about, there have to be sacrifices. And Angel has to make his sacrifice, just the same as Barney would make, if their places were reversed. Get Angel off, and what have you proved? That there’s no prejudice in San Juno. In the whole State, for that matter. But that’s not true. There is prejudice. The kind that’ll railroad a Mex to his death on a charge that wouldn’t take a white man past the coroner. That’s the truth. And to bring that truth into focus, to prove it, the prejudice has to be permitted to do its work, to do its murder right out in public, where it will drive the truth home to the people who have to be brought together and united, to fight the prejudice, so that it won’t be here any more and the new world will be here. Only— . . . of course Angel won’t be here to enjoy that wonderful stinking day.28

Although the novel deals harshly with racists and the un-American activities committees; the main criticism of the Mankiewicz work is directed at the Communists. The author, foe of both right and left, received the applause of liberals.

Trial represented a qualitative change in Scottsboro literature. In the 1930s a considerable quantity of Scottsboro material was produced, and it overwhelmingly represented the radical perspective. Much of it was published in the Communist press—the Daily Worker or New Masses. But even Wexley’s play, the poems in the Urban League’s Opportunity, and Harlow’s account in the NAACP’s Crisis, all reflected a radical outlook. In each, Negroes are unjustly persecuted by a racist society; in each, the judicial system is viewed with hostility—either because of a Pilate-like judge or a sadistic jury. In each example the author’s main target is racism in America, and in some works Communists emerge as heroes—the vanguard against racism.

With the 1950s American intellectuals, reflecting the new climate of anti-Communist liberalism, could no longer accept such a view. Trial was written; Trial won acclaim; Trial was filmed. Here was the Scottsboro case, though warped, distorted, liberalized. Whereas previous efforts had questioned the possibility of justice in a racist society and attacked American racism, Mankiewicz posed no such questions and directed his attacks elsewhere. In his novel, racists exist. But who arouses them, who works with them? The Communists. In his novel an innocent man is condemned, an injustice occurs within the system. But who is at fault? Not the system, but the Communists. The theme of Trial is nearly the reverse of previous writings on Scottsboro. Most previous authors had blamed the injustice on the system and some looked to Communists to right the wrongs; Mankiewicz blamed the injustice on the Communists, who for him were the great threat, the great danger. So if somehow justice in America malfunctioned, the Communists were somehow to blame. Liberals no less than conservatives have found in Communists a convenient scapegoat.

When Mankiewicz wrote Trial, he significantly changed the race of the accused from black to brown, the State from Alabama to California. The reason is evident. If the liberal is to blame injustice on the Communists, the accused minority must have a chance of acquittal before his perfidious radical attorney places him on the witness stand to betray him. But the accused at Scottsboro had no such chance. Many blacks still have no chance. Thus, Mankiewicz wrote of a Mexican on trial in California rather than of blacks on trial in Alabama.

Interesting as this liberal anti-Communist novel is, its charges against the Communists basically are unfounded. It is an interesting novel not because of what it reveals about Scottsboro, but because of what it shows of the liberal psyche. As late as 1955, liberals preferred to avoid the issue of the black man—sublimating him into a Mexican, an Indian, or some other more palatable minority. Moreover, Trial assured Americans that the system was sound, except when villainous radicals tampered with it. And in the film, in the tradition of Hollywood’s happy endings, the liberal lawyer even challenges the Communist Castle and succeeds in saving young Chavez.

What Mankiewicz did for cold-war fiction, scholars have done for cold-war history. Liberal historians manufactured a myth about Scottsboro so that the case became an anti-Communist morality play. According to liberals, Communist treachery was revealed in a number of ways. First, Communists stole large sums of money contributed to the defense of the young blacks. Allan Knight Chalmers maintained that Communists collected over $1,000,000 in the name of the boys, but spent only $100,000 on their behalf.29 Murray Kempton, Ralph McGill, Walter White, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., good liberals all, all re-echo Chalmers’ charge.30 In addition, others have elaborated, but in the fashion of medieval historical exaggeration. Quentin Reynolds implied that the Communists profited by $2,000,000, while the president of a Negro college escalated the amount to $5,000,000.31 Oneal and Werner, describing American Communism, discussed Scottsboro in their chapter on finance rather than minorities!32 Nevertheless, Dan Carter in his prize-winning study, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South, published in 1969 after the apex of the cold war, wrote:

There is little evidence to support the constantly reiterated charge that the Communists raised as much as one million dollars from the case. . . . The proletarian nonchalance with which the International Labor Defense kept its records makes definitive conclusions difficult, but the ILD’s financial reports and other internal evidence indicate the Party and its affiliates raised less than $150,000 with the great majority of this amount going to unavoidable defense costs.33

Regrettably, Carter buries this revisionist analysis of the liberals’ oft-repeated charge in the second half of a footnote, thereby insuring the continued repetition of the charge.

Another liberal charge which Carter refutes is the contention that Communists sought to have the black defendants executed in order to create martyrs, intensify distrust of the American judicial system, and, in the process, win more converts to Communism. Ironically originating with W. E. B. DuBois in 1931, the charge, in modified form, can be traced to Wilson Record, William Nolan, James Farmer, and J. Edgar Hoover.34 Concerned with motivation rather than action, this charge is more difficult to disprove. Nonetheless, after recording many of the anti-Communist allegations, Carter concludes: “No amount of reservations or criticism, however, could alter one basic fact. The International Labor Defense had succeeded in winning eight of the Scottsboro boys another chance for life.”35 Had the Communists truly desired the deaths of the blacks, they most likely never would have intervened in the case at all.36 The only reason people heard of the case in the 1930s and remember it in the 1970s is because the Communists did intervene and did make of it a cause célèbre.

The literary monopoly of anti-Communist liberals was challenged slightly with the advent of major civil rights and anti-imperialist movements in the 1960s. Even classic cases of American injustice could again be discussed, could again be topics of literature. In 1969 Dan Carter’s rather objective book was published and won acclaim. In 1970 Kelly Covin published Hear That Train Blow!, a “documentary novel” of the Scottsboro case.37 Appearing a year after Carter’s work, it is interesting to note where Covin’s novel deviates from historical fact—for deviations there are. First, Covin implies there was considerable publicity about the Scottsboro case before the Communists controlled the defense.38 True, but the early publicity was concerned not with exposing Alabama injustice but with praise for the State for preventing a pre-trial lynching.39 Second, in contrasting the NAACP attorney and the ILD attorney, Covin maligns the latter.40 In so doing, Covin obscures the fact that the United States Supreme Court in 1932 granted new trials, to the Scottsboro defendants, because of the incompetent defense of the NAACP attorney. Had the NAACP conducted the appeals instead of the Communist ILD it is possible the innocent Negroes would have been executed.41 In a similar vein, Covin portrays the appeal to the Supreme Court as almost automatic,42 grossly underestimating the difficulties in appealing to the conservative court of 1932.43 He accuses the Communists of making enormous profits by diverting funds contributed to the defense,44 a repetition of a falsehood. Ironically, while alleging that the ILD was siphoning off funds raised in America, he also identified the ILD as a “Moscow financed” organization.45 Finally, Covin accuses the Communists, like Bernard Castle in Trial, of seeking the death of the Negroes for propaganda purposes.46 The refutation of this has been presented already.

There are other historical errors in Covin’s work, but it is unnecessary to catalog the way in which a novel is not history. My purpose in revealing the aforesaid distortions is to demonstrate that Covin’s novel incorporates much anti-Communist prejudice. However, one character created by Covin, indeed the hero of his novel, is of special importance. Hector Benson, a reporter for Southern newspapers, follows the rape case from the outset and even prompts prison guards to obtain “confessions” from the accused Negroes. But as the trials and years elapse, Benson sickens of the injustice and resolves to struggle for a more just society, for a better world. He becomes a reporter for the Daily Worker, volunteers for Spain, and is killed in that nation’s civil war. It is Benson, the Southerner, the Communist, who lives the “American dream.”47 Thus, the breakthrough in Covin’s novel is that he defies the blacklist on Red heroes and portrays an American Communist as a most noble American.

The Covin novel of 1970 is a contradictory synthesis, a hybrid of the 1930s and 1950s, straddling the ideological issues raised by Scottsboro. Hear That Train Blow! contains much anti-Communist propaganda, but partially counters it by including many historical documents. Surprisingly, it makes a Communist the hero of the novel. Nonetheless, Covin retains so many false accusations against the Party that most readers will, like the hero’s wife and his boss, find his conversion to Communism inexplicable. Though Hear That Train Blow! is an excellent short account of prejudice in the South, it is also a synthesis of compromise between the truth of the Scottsboro case and the necessity of the American market place.

Countee Cullen erred when he accused the poets of silence about Scottsboro. Poets did sing, and playwrights did write. But in the era of mass communication more was required if those voices were to be heard. Only Trial has been fully acceptable to the mass media, because only Trial deflected the Scottsboro theme from an attack upon racism into an attack upon Communism. Only then was the Scottsboro story acceptable to the media, but it was so distorted as to be almost unrecognizable. Perhaps it is not the poets but the media and those who control it who are responsible for the silence surrounding Scottsboro.

Notes

1 For example, see Walter White, How Far the Promised Land? (New York, 1955), p. 215. For the best general account of the entire case see Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge, 1969).

2 Countee Cullen, “Scottsboro, Too, Is Worth Its Song,” in Black Voices: An Anthology of Afro-American Literature, ed. by Abraham Chapman (New York, 1968), p. 385.

3 Langston Hughes, “Scottsboro Limited,” New Masses, VII (November, 1931), 18-21. It is surprising to find Ezra Pound, in a letter from Italy, thanking Hughes for sending him a copy of the play. Pound related, “As for the case itself, [sic] I don’t know that my name or anyone’s name can be of any use.” He then stated that the South was governed by its worst men, giving birth to “flagrant injustice.” D. D. Paige, ed., The Letters of Ezra Pound: 1907-1941 (New York, 1950), p. 241.

4 Hughes, “Scottsboro,” Opportunity, IX (December, 1931). 397; “The Town of Scottsboro,” New Masses, VII (February, 1932), 174; “Brown America in Jail: Kilby,” Opportunity, X (June, 1932), 174; “My Adventures as a Social Poet,” Phylon, VIII (Third Quarter, 1947), 207-08. A number of Hughes’ works on Scottsboro were printed in a pamphlet, Hughes, Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play in Verse (New York, 1932).

5 S. Ralph Harlow, “It Might Have Happened in Alabama,” Crisis, X (October, 1933), 27-29. Harlow was asked if his opinion of the jurist had changed after Judge Horton reversed the jury’s verdict of guilty and remanded the case of a Scottsboro boy to a new trial. To this Harlow replied, “Judge Horton did ‘score’ but “ . . . he hardly should be given credit for any great victory, either in the realm of law or of ethics, . . . At least he should have broken in several times and denounced the tirades delivered. . . at the trial; on two counts he could have called the trial off and his final words of praise to the jury after they reached their verdict washed out for me all he did to preserve order in the court room.” Judge Horton undoubtedly displayed courage by overturning the jury’s guilty verdict. As a consequence, he was defeated when he sought reelection to the bench. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that Judge Horton knew the boys were innocent. One of the doctors who had examined the girls shortly after the alleged rapes told the judge in 1933 that they had not been raped. The judge, like the doctor, remained silent about this incident from the 1930s until the 1960s. See Carter, Scottsboro, pp. 214-15; also my interview with former Judge James E. Horton at Greenbriar, Alabama, July, 1967. Regrettably, C. Vann Woodward, reviewing Carter’s book, deemed Judge Horton the hero of the case. C. Vann Woodward, New York Times Book Review, March 9, 1969.

6 Muriel Rukeyser, “The Trial,” New Masses, XI (June 12, 1932), 20.

7 New York Daily Worker, November 24, 1934; Ibid., May 4, 1936; Kay Boyle, “A Communication to Nancy Cunard,” New Republic, XCL (June 9, 1937), 127.

8 New York Times, March 4, 1934. The play can be found in: John Wexley, They Shall Not Die: A Play (New York. 1934); Granville Hicks, et al., Proletarian Literature in the United States (New York, 1935); and Burns Mantle, ed., The Best Plays of 1933-1934 (New York, 1935), p. 228.

9 Elmer Anderson Carter, “They Shall Not Die,” Opportunity, XII (April, 1934), 118-19.

1010 J. K. , “The Theatre,” New Masses, X (March 13, 1934), 30.

11 “They Shall Not Die,” Crisis, XII (April, 1934), 104.

12 Morgan Y. Himelsteil, Drama Was a Weapon: The Left-Wing Theatre in New York, 1921-1941 (New Brunswick. N.J., 1963), p. 189. It is alleged that Sasha Small, one of the editors of the official ILD journal, wrote another play, “Scottsboro,” which was produced in large American cities. See U. S. Congress, House, Special Committee on Un-American Activities in the United States, 75th Cong., 3rd sess., 1938, p. 502. Nevertheless, the only work by Sasha Small that I could locate was Scottsboro: Act III, a fifteen-page pamphlet.

13 T. S. Stribling, Unfinished Cathedral (Garden City, 1934).

14 New York Daily Worker, July 21, 1933.

15 Ibid., March 6, 1937; Hicks, Proletarian Literature, pp. 207-08.

16 New York Daily Worker, March 3, 1934. Also, there was a suggestion by Floyd C. Covington, Executive Secretary of the Los Angeles Urban League, that a movie be made with these objectives: 1) raise money for the Scottsboro defense, 2) develop sympathy for Negroes, and 3) give every Negro an opportunity to participate in something of interest to him. But Covington proclaimed that this proposed film was “not one of propaganda or reciprocal prejudice and hatred; for he who would reach the hearts and minds of men must use an alchemy of love and forbearance. Only a theme which has human interest, a universal, and non-propagandistic motif can accomplish this.” Apparently Covington believed the Scottsboro case lacked such interest and motif. He proposed instead a story of a Negro boy who joins a circus. Floyd C. Covington, A Motion Picture Project for Scottsboro Boys Defense Fund (Los Angeles: Urban League, 1933). In addition, there was at least one attempt to use the Scottsboro story as the basis of a television production in North America. Whether it was ever televised, I do not know. See letter of Kelly Covin of Alan Reitman, September 14, 1964; “The Thirteenth Juror: A Television Documentary-A Study in Prejudice Based on the ‘Scottsboro’ Writings of Arthur Garfield Hays, and on Court Records,” American Civil Liberties Union Files, New York City. Ironically, the British commercial television network, ATV, presented on July 11, 1972, a fifty-two minute program on the Scottsboro case. The telecast was part of ATV’s “turning points in history” series, with another in the series devoted to the battle of Dien Bien Phu. In April, 1976, the National Broadcasting Company telecast a television film, “Judge Horton and the Scottsboro Boys.”

17 For an account of the tedious negotiations between the SDC and Alabama Governors, as well as internal conflicts in the SDC, see Allan Knight Chalmers, They Shall Be Free (Garden City, 1951). The introduction was written by the anti-Communist Walter White of the NAACP. Chalmers had chaired the SDC; his attitude to the Communists pervades his book, and can be summarized in his own words on p. 131:

Frankly, I hate to contemplate the vials of wrath, the vitriolic bitterness, and the restoration to control over the defense of those [the Communists] whose belief that it is only by denunciation and violence that justice can be obtained. It is . . . that a part of my great concern in this matter has been to demonstrate the effectiveness of the way of working through conciliation in the solution of an apparently insoluable situation.

18 Ibid, p. 219.

19 New York Times, June 7, 1950.

20 T. L. Langhorne. review of Scottsboro Boy, by Haywood Patterson and Earl Conrad in Journal of Negro History, XXXV (October, 1950), 464.

21 Ibid., p. 465.

22 Abner Berry, “American Dachau,” review of Scottsboro Boy by Patterson and Conrad, in Masses and Mainstream (July, 1950), pp. 83-6.

23 New York Times, June 8 and July 11, 1950; Chalmers, op. cit., p. 222.

24 New York Times, July 14, 1950.

25 Ibid., August 2, 1949.

26 Paul Maas, “The Tragic Curse of the Scottsboro Boys,” Inside Story (May, 1960), pp. 16ff; Sally Belfrage, “The Scottsboro Boys Today,” Fact, III (November-December, 1966), 58-62; Carter, Scottsboro, pp. 414-16.

27 Don Mankiewicz, Trial (New York, 1955; paperback edition, 1962). p. 163.

28 Ibid., p. 235.

29 Chalmers, op. cit., p. 34.

30 Murray Kempton, Part of Our Time: Some Ruins and Monuments of the Thirties (New York, 1955), p. 253; Ralph McGill, The South and the Southerner (Boston, 1959), p. 198; White, op. cit., pp. 214-15; Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., The Politics of Upheaval, Vol. III: The Age of Roosevelt (Boston, 1960), p. 429.

31 Quentin Reynolds, Courtroom: The Story of Samuel S. Leibowitz (New York, 1950), p. 311; Broadus Butler in a speech to faculty at Dillard University, New Orleans, September, 1969. The anti-Communist Harold Cruse simply quotes Reynolds. See Harold Cruse, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, from Its Origins to the Present (New York, 1971), p. 148.

32 James Oneal and G. A. Werner, American Communism: A Critical Analysis of Its Origins, Development and Programs (New York, 1947), pp. 234-35.

33 Carter, op. cit., p. 170. For further refutation of this charge that Communists stole vast sums see Hugh Murray, Jr., “The Scottsboro Rape Case and the Communist Party” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Tulane University, 1963), pp. 242-45. See also Hugh T. Murray, Jr.’s Civil Rights History-Writing and Anti-Communism: A Critique (New York; American Institute for Marxist Studies, Occasional Paper, 16, 1975), pp. 26-32.

34 W. E. B. DuBois, “Postscript,” The Crisis, XXXVIII (September, 1931), 313: Wilson Record, Race and Radicalism: The NAACP and the Communist Party Conflict, vol. of Communism in American Life, ed. by Clinton Rossiter, and vol. of Cornell Studies in Civil Liberty (Ithaca, 1964), p. 43. Earl Latham, The Communist Controversy in Washington: From the New Deal to McCarthy (Cambridge, Mass., 1966), p. 25; James Farmer in a speech at Tulane University, February, 1964; J. Edgar Hoover, Masters of Deceit: A Study of Communism in America and How to Fight It (New York, 1958), p. 252; Thomas R. Brooks, Walls Come Tumbling Down: A History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1940-1910 (Englewood Cliffs, 1974), p. 68.

35 Carter, op. cit., p. 173. Similar conclusions were drawn by the correspondent of the New York Times who attended many of the trials, New York Times, January 20, 1936.

36 Hugh T. Murray, Jr., “The NAACP Versus the Communist Party: The Scottsboro Cases, 1931-1932,” Phylon, XXVIII (Fall, 1967), 287.

37 Kelly Covin, Hear That Train Blow! A Novel about the Scottsboro Case (New York, 1970). Discussion of anti-Communist prejudices in Carter’s work will be discussed in Hugh T. Murray, Jr., Civil Rights History and Anti-Communism, Occasional Paper, no. 16, American Institute for Marxist Studies. Forthcoming, 1975.

38 Covin, op. cit., p. 24.

39 Carter, op. cit., p.13; New York Times, March 26-31, 1931.

40 Covin, op. cit., pp. 137-38, 157-58, 150, 199.

41 Murray, op. cit., pp. 286-87.

42 Covin, op. cit., p. 195.

43 Murray, op. cit., pp. 284-87.

44 Covin, op. cit., pp. 205, 235, 295, 373. 374.

45 Ibid., p. 29.

46 Ibid., pp. 31, 199, 236, 295.

47 Ibid., pp. 435-37.

Posted March 15, 2007