AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

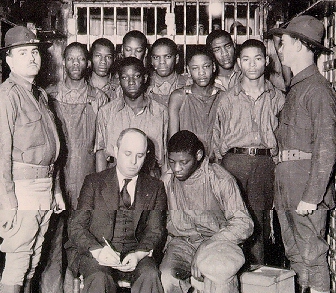

From Science & Society, 35:2, Summer 1971, 177-192. Elsewhere on this site are Murray's "The NAACP versus the Communist Party: The Scottsboro Rape Cases, 1931-1932" (cited in the 5th reference note below); his "Changing America and the Changing Image of Scottsboro"; and his 2002 letter on Scottsboro.

Aspects of the Scottsboro Campaign

Hugh Murray

Gilbert Osofsky observed that “next to the trials of Sacco and Vanzetti and perhaps the Rosenbergs, the Scottsboro case was the most prominent international cause célèbre in American history.”1 Certainly, it was the most famous rape case of the century. In Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South, Dan T. Carter superbly recounted the legal intricacies of this complex case,2 but fully as important as the courtroom drama and secret negotiations with Alabama governors was the campaign of agitation organized by the International Labor Defense (ILD).

On March 26, 1931, a posse of two hundred whites pulled nine young blacks from a freight train in northern Alabama, accused them of the rape of two white girls who had been hoboing on the same train, and nearly lynched the Negro youths. However, persuaded to rely upon legal processes,3 the white populace waited two weeks to literally applaud the court’s action whereby eight of the Negroes were sentenced to death in the electric chair.4 By May, 1931, a struggle to control the Negroes’ defense erupted between the liberal National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Communist ILD. One point of dispute between these two organizations was the role assigned to “mass action”: while the NAACP generally opposed large demonstrations, parades, and protest rallies, the ILD promoted such agitation.5 The purpose of this article is to review some of the aspects of the Scottsboro protest agitation, with emphasis on that movement in the South.

As early as April, 1931, the Communist Daily Worker began extensive coverage of the “frame-up”—so extensive for so many years that William Nolan concluded: “the amount of space allotted to it [the Scottsboro Case] was almost incredible . . . the reader of the Daily Worker might have gotten the impression that nothing else mattered to the communists, so many were the columns devoted to the case.”6 Henry Moon concluded that the cause of the youths “was second only to the defense of the Soviet Union on the party agenda.”7 The Scottsboro case was to be the most effective campaign conducted by the Communists among Negroes, and it raised the ILD to prominence as a defender of black rights.8 Indeed, the previous efforts by the Communists in the Negro community had been so meager that one might assert that Communist agitation did not begin among blacks until the Scottsboro case.9 Soon after the ILD dispatched attorneys to Alabama, the Central Committee of the Communist Party, U.S.A., issued directives to the general membership concerning the rape case. Through the establishment of local neighborhood committees focusing upon the Scottsboro issue, and by supplying speakers to interested clubs, churches, and unions, the Party hoped to gain non-Communist support for its defense effort. To insure fulfillment of this directive, from two to four members of each Party unit were assigned to ILD and League of Struggle for Negro Rights activities. These comrades were to be supervised in their work by a director chosen from each section.10

When organizations called upon an ILD speaker, the theme he stressed, aside from highly specific contentions that changed with the events of the cases, was the universality of Scottsboro. “The life of the Negro people today is a thousand bloody Scottsboros,” wrote James W. Ford, the Negro Communist candidate for Vice-President in the 1930s.11 Henry ‘Winston emphasized that under capitalism additional Scottsboros would occur. With nothing to do, the unemployed Negro youth of America stood idling on street corners. Some might seek escape by hoboing to another community in search of work. Winston warned young blacks, however, “You are liable to get pulled off of a freight-train and sent off to jail or a chain gang for the crime of looking for work. You are running the risk of becoming another Scottsboro boy. Any Negro is in danger of becoming another Scottsboro boy.”12

The Communist leader, Earl Browder, maintained that despite the universality of Scottsboro, there was something unique about these trials. The Scottsboro case differed from the numerous similar examples of Southern “justice,” he said, because the Scottsboro boys had selected the ILD to defend them. Had liberals or socialists conducted the defense, the case would have remained unnoticed and the boys electrocuted. What distinguished Scottsboro from thousands of similar cases, he maintained, was the militant defense and agitation sponsored by the ILD.13

The Scottsboro agitation was most impressive. Albert Einstein, Maxim Gorki, Mme. Sun Yat Sen, Jomo Kenyatta, André Malraux, and Theodore Dreiser all petitioned for the release of the defenants.14 On a single day there were Scottsboro demonstrations in San Salvador, Johannesburg, Montevideo, Santo Domingo, and Santiago de Cuba. Accra, now the capital of Ghana, reported at least one rally, and in Newcastle the mayor participated in the protest. A collective farm in the Soviet Union was christened “Scottshoro.”15 The radical Frenchman Daniel Guerin reported that Communists “did a splendid job of pillorying American racism for all the world to see.”16 The NAACP’s Walter White ruefully admitted the same fact when he wrote, “undoubtedly more harmful . . . was the effective use by the Communists all over the world of the Scottsboro case to vilify American democracy and to create distrust of it, especially among the dark-skinned peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America.”17

Within the United States the Party’s Scottsboro campaign was chiefly directed toward the Negro people. Communists viewed the Scottsboro case as an opportunity to emerge as the champion of the oppressed. To some degree they were successful.

By 1933 Lawrence Reddick reported that the Scottsboro agitation “had made some dent” on Negro students.18 Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) quoted a Southern educator as stating, “There’s too much rabbit in most of us and this Scottsboro case has taken a lot of rabbit out and made us fight.” Baldwin was also informed that Negro students had gained hope and courage as a consequence of the Scottsboro campaign.19 Even respectable Negro fraternities passed resolutions on the case,20 while in Philadelphia hundreds of school children struck on behalf of the Alabama defendants21—a minor precursor to the school boycotts of the 1960s.

Not only students were stirred by the Scottsboro case. The editor of the Negro Houston Informer and Texas Freeman noted that many downtrodden blacks had become favorably disposed to the Communists because of their efforts to save the Scottsboro boys.22 The editor of another Negro paper, the Louisville Leader, observed that the Scottsboro case, along with integrated parties and eviction protests, “would advertise Communism, recommend it highly, and make a strong appeal to a certain number of a much abused race.”23 This appeal was certainly strong to Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., son of the prominent Atlanta Republican family, who joined the Communist Party in January, 1933. He recalled that “my impression of the Communists was formed during the period of Scottsboro—the case which epitomized the plight of the Negro and the correct policy of the Communist Party. . . .”24 Even Asbury Smith, Baltimore minister and member of the executive board of the Urban League, was impressed sufficiently to assert that “the Communists go out and fight for Negro rights. The International Labor Defense is Communism in action for Negro rights and Scottsboro is the supreme example.” He concluded, “The International Labor Defense can and will do much good for the Negro.”25

Of special significance was the amicable relationship established between the Communist Party and various Negro churches as a consequence of the Scottsboro agitation. This relationship was important to the Party, because the church was the most salient and unifying force in the life of the American Negro.26 Prior to the Alabama “rape” case, the Communists had often denounced religious institutions, including Negro churches, on ideological grounds; these attacks diminished shortly after the ILD entered the Scottsboro case, and the Daily Worker reported sizable religious support of the effort to save the accused Negroes.27 Radical attacks upon churches were soon limited to those congregations that endorsed the NAACP and refused to allow the ILD to present its view. In Chattanooga, Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, indeed, throughout the nation, leading Negro churches became centers where Communist spokesmen pleaded on behalf of the Scottsboro boys. The Party representatives listened to the opening hymns, the prayers, and the preachers; and in return for the opportunity to address the meeting and collect funds for the defense, they de-emphasized their atheism.28

It was from the sympathetic Negro churches that the United Front Scottsboro Committees largely recruited members and supporters. In turn, it was through these specifically Scottsboro fronts that the Communists were able to receive their first hearings before Negro clubs, unions, and additional Negro churches. Not all ministers were disposed to invite Communists to their churches, but many acquiesced because “the colored ministers were afraid not to co-operate with a movement which aroused such deep-seated emotions among their followers.”29

The Negro churches themselves became an agency for recruiting members into the Party,30 and Communists debated whether they should abandon entirely their anti-religious program.31 Thus, Earl Browder declared:

We judge religious organizations and their leaders by their attitudes to the fundamental social issues of the day. . . . We would be delighted if thousands of other churches would support the Workers Social Insurance Bill, the fight to free the Scottsboro boys. . . .32

The temper of the South concerning the case can best be gauged not only by the exuberant crowd celebrating the conviction of “rapists,” but by the attitudes openly manifested in subsequent editorials and news items. For example, the Jackson County Sentinel, published in Scottsboro, reported on May 21, 1931:

Two foreign looking guys dropped into town Wednesday . . . and introduced themselves as reporters from the New York Times wanting information and “dope” on the [Scottsboro] negro [sic] case. They showed supposedly good credentials, but both were sort of Russian-looking and they soon collected a crowd of local people who had a suspicion they were meddling Reds. They called at the Sentinel office to look over the files . . . later the two strangers were picked up in a Ford roadster by two other strangers and they tore out of h ere without even goodbye. . . .

One of them asked me what the crowd was following them for and I told them they thought they were Reds. They might have been Reds (they were not from the Times) but they sure looked white then. From now on, strangers with Russian accents and long hair better stop over at Chattanooga and just read about us.

The editor of the Sentinel continued his amusing theme a week later (May 28):

Haven’t heard anything more on our. . . “New York Times” reporters who . . . left about thirty minutes ahead of a telegram proving them fakes. I shall always remember how homesick that long-haired boy looked when fifteen local mountaineers asked to see his credentials.

While the editor of the small-town weekly chuckled, the editor of the respectable Chatanooga Times (May 21, 1931) printed a potentially much more dangerous story about the visitors to Scottsboro, for it concluded with this advice to mountaineers and others, under the heading “New York ‘Reporters’ Believed Imposters”:

They were travelling in a Ford roadster with rumble seat. All were foreigners. One of them wore glasses and a gray suit. He had a prominent nose. The driver of the car was red-headed, while a third was hatless and possessed a heavy head of black hair. Description of the fourth was not available.

Another interesting example of Southern attitudes can be observed in this rather lengthy account in the July 23, 1931, Jackson County Sentinel:

Two Alleged Reds Visit Scottsboro

Scottsboro had visitors last Saturday night and Sunday. The Reds, themselves! . . .

Saturday night a man and a woman, nicely dressed and well-educated hitch-hiked into town and registered at the Bailey Hotel as Mr. and Mrs. _______ of Washington. They strolled about town and engaged several negroes [sic] in conversation, the negroes state, inquiring about the trial and case here. . . .

One of the negroes to whom they talked reported the matter to a white man and Sunday morning Sheriff Wann picked up the couple at a filling station in town at which they said they were waiting to catch a ride out of Scottsboro.

They were taken to the jail and their baggage searched and it was found they had a number of pieces of red literature and correspondence with Communist headquarters in New York and other places. . . .

The woman had been keeping a diary in German and it was carried to a local yong lady who interpreted it but could find nothing in it . . . but was evidently a personal affair. . . .

They were held at jail for a couple of hours and seemed badly frightened . . . . Immediately after being taken to the jail the man . . . asked that he might be allowed to send some telegrams and he gave wires to be sent to a Congressman in Washington and other persons New York and elsewhere. However, the Sheriff did not send the wires . . . .

He stated that both he and his wife were teachers and had come to Scottsboro out of curiosity and had made no effort at any kind of organization, yet they admitted talking to several negroes and did not deny they were communists. . . .

After conferring with attorneys and other higher officials and having no direct evidence that either . . . had organized any negroes here and believing that it was best for all concerned to release them and send them on their way before any violence might occur, the Sheriff released the couple and offered . . . to transport them outside the town. . . . They said they wished to continue on their way to Mexico . . . but before they left the fail here they went through their baggage at the suggestion of officers, and destroyed all the Communist correspondence and literature that might give them trouble again.

The man and the woman shook hands with the sheriff a number times and were profuse in their thanks, and Sheriff Wan said to them:

“You are very unwise to come here . . . or attempt to agitate negroes or even as an outside. . . . We are giving you protection and sending you safely away; regardless of what the Reds say about us, we have never been unfair to strangers, either negro or white. . . .”

. . . However, under the circumstances the sheriff and officials, we believe, pursued the wise course at this time in sending them on their way unmolested. . . .

It may be this act was not satisfying to many of our citizens, and it could be hardly fully satisfying to any citizen of this town or county, yet it may have avoided world-wide ridicule and vicious attacks not confined to words and literature.

When in Scottsboro even a well-dressed white couple could be taken to jail because they conversed with Negroes, this warning in the Jackson County Sentinel, of August 6, 1931, was ominous:

. . . but the local white and colored races seem to be on terms of good understanding and friendship. We seriously feel but a very, very few local negroes could be persuaded to join the Communist ranks. The real trouble lies in the percent of negroes who are also enemies of their own race getting wrong kinds of notions in their heads. In Scottsboro the larger per cent of the negroes are much more afraid of dangerous and criminally inclined members of their own race than they are of any white people anywhere.

However, it is well for all negroes in this community to understand at this time that no Communist activity will be tolerated here and if they get in trouble along this line they cannot expect sympathy from white sources so many times loyal in answering “the trouble call.”

With such attitudes dominant in the South, the task of the Scottsboro defenders was most difficult. Nevertheless, some radicals dared to rouse the racist wrath. Langston Hughes visited Tuskegee Institute in Alabama soon after the Scottsboro case had begun; there he did not hear Scottsboro mentioned. While at Oakwood Junior College, near Huntsville, Hughes revealed his desire to interview Ruby Bates, one of the victims of the Scottsboro boys’ alleged assault. It was then rumored that Miss Bates had changed her story and denied that any rape had occurred (indeed, she was later to become the principal defense witness). Warned that he would receive no cooperation from Negroes at Oakwood and persuaded that his endeavors might endanger the college, Hughes abandoned his project.33 He then traveled to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he addressed various groups on the white campus. The daily Tar Heel noted that “his poetry as well as his speaking is the expression of a clear and sincere spirit.”34 But the Charlotte Southern Textile Bulletin deemed his speech a clear and present danger. Before the white college students, Hughes had announced:

For the sake of American justice (if there is any) and for the honor of southern gentlemen (if there ever were any) let the south rise up in press and pulpit, home and school, senate chambers and rotary clubs and petition the freedom of the doomed young blacks so indiscreet as to travel unwittingly on the same freight train with two white prostitutes. . . .35

Hughes’ speech was reprinted in the recently founded radical magazine in Chapel Hill, Contempo, edited by Anthony Buttita. When a traveling salesman brought a copy of Contempo to the editor of the Jackson County Progressive Age in Scottsboro, the Alabama editor fumed:

The article was written by a member of the Communist party . . . and pertains to the eight [Scottsboro] negroes . . . . It contains statements in it that are scandalous and blasphemous and we are surprised that a Southern institution would allow such articles printed . . . . We thought once of printing the article in question . . . but it is so nasty and dirty that we do not want it to appear on our pages, especially where children would read it. The writer, Langston Hughes, takes a shot at the South for its attitude toward social equality and hints that our judge permitted a farce trial and reflects on the jury and the court officials.36

Southern intellectuals were not the only ones enraged by Hughes. While in North Carolina, Buttita and some friends accompanied Hughes to a drug store where all ordered food and were served. When the waiter realized that he had erred in thinking Hughes a Mexican, he wanted to punch the black poet in the nose.37

Some years later Hughes described his experience speaking in the South in an article, “Cowards from the Colleges.” Hughes reported that not a single Tuskegee student had attended any of the Scottsboro trials. While Scottsboro protestors demonstrated around the globe, not one demonstration had occurred on a Negro campus in Alabama.38 Two racist apologists for the Southern way of life gloated: “Tuskegee Institute, the most cultured negro educational institution in the world, has remained aloof from Scottsboro case throughout its spectacular history.39 Actually, Tuskegee had not aloof; many of its leaders strove to stifle Scottsboro protests in Alabama.40

If the colleges were cowed, a considerable number of Southerners outside the academic community were not. As early as May 30, 1931, an All-Southern United Front Scottsboro Defense Conference of two hundred delegates was scheduled for Chattanooga.41 Only fifty miles from Scottsboro, the Tennessee city had on April 3, 1931, convicted a white Communist, Mary Dalton, for inciting to riot, but a fortnight later the ruling against her was reversed; thus of all the potential sites in the South, the Communists were probably wise in choosing Chattanooga for their gathering.42

When the Southern Conference began, some of its leaders were arrested for loitering after they had dared stroll, black and white, down a Chattanooga street.43 Mrs. Bessie Ball, a black lady from that city, had been elected as a delegate to the Conference—a meeting condemned by the NAACP and the local ministers’ alliance. Mr. Ball, stirred by one of the anti-communist divines, discovered his wife’s intention to attend the radical conclave, and beat her. Their daughter had him arrested, but when his case came before the court, “the judge congratulated him on his conduct and advised him to use a shotgun on the Reds and call the police if they gave him any trouble. The wife was fined.” Mr. Ball next hit a neighbor on the head with a wooden block and wounded another with a shotgun. His victims were imprisoned, but he remained free.44

With such punishment for seeking freedom and such rewards for collaboration, it is not surprising to discover many “Negro leaders” saying what whites wanted to hear. A few days following the conclusion of the All-Southern Scottsboro Conference, William Pickens, field secretary of the NAACP, spoke in Chattanooga. When two workers demanded the floor to present ILD views, they were immediately arrested.45 The Chattanooga Times (June 8, 1931) extensively reported Pickens’ address under the headline: “Negro Speaker Warns Against Red Campaign. Dr. Pickens Cites Activities in Scottsboro Case.” Moreover, Pickens’ speech provided the basis for an editorial in the June 9, 1931, Chattanooga Times that was republished in the June 11, 1931 Jackson County Sentinel:

Negro Leader Sounds Warning

Southern people would do well to heed the warning of Dr. William Pickens, colored, field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, that communist activities among Negroes constitute a serious menace to the South. “This Communist sapping through the densely ignorant portion of the colored population, while not immediately menacing to government itself, is certainly most menacing to good race relations . . . .”

In a similar tone, the Chattanooga Ministers’ Alliance devoted its radio program to good race relations and denounced the Communists for attempting “to tear the South asunder and destroy the peace and harmony existing for many years.”44 The May 21, 1931, Jackson County Sentinel happily published a “Letter From Pastor of Local Negro Church,” who wrote in reply to a letter from a white Philadelphia Communist printed in the same paper:

Donald Greer does not know the facts in the case. What does a man of his make-up care about facts. He denounces the South as nothing but a lynching part of the country, which is a lie from the deepest hell.

The racial troubles. . . is caused by the ignorance of both races. . . .

Those eight boys if guilty should be dealt with according to law, and personally I believe they have been given a fair trial and I speak the sentiment of the better class of negroes when I say such. Harmony, peace and good will and understanding prevails among the races in Scottsboro [emphasis mine-H.T.M.]. There will be some of my race who perhaps will read this letter and say some unkind things, and think I have been urged by some whites to write in order to stand in their good graces which is not true. No one asked or urged. . . . For after all there is one race, the human race.

The culmination of this reactionary criticism occurred after the Camp Hill-Dadeville incidents of July, 1931, in which at least one Negro was killed in central Alabama. Dan Carter described the events and concluded:

Not one Alabama newspaper pointed out that, far from being a bloody Negro race riot, it was the whites who formed mobs and terrorlzed the countryside . . . . the press and local officials seemed intent on proving to the satisfaction of everyone that the local Negroes were bent on raping and killing the whites of the community. The real crime of the hapless Negroes was simply their effort to organize. Local whites correctly saw this as a threat to the status quo. Any effort to give the Negro tenant a voice . . . was essentially “revolutionary.” At heart Tallapoosa white citizens knew that the movement also threatened the existing biracial relationship. Thus they were unduly concerned about the sharecroppers’ stepping “out of their place” in protesting the Scottsboro verdict.47

The Communists, the ACLU, the Urban League and others vigorously denounced the white racists for their intimidation.48 The NAACP, however, blinded by anti-communism, echoed the line of the southern white power structure. W. E. B. Du Bois expressed the NAACP position on the Camp Hill-Dadeville incidents in Crisis:

. . . black sharecroppers, half-starved and desperate, were organized . . . and then induced to meet and protest Scottsboro. . . . If this was instigated by Communists. . . it is too despicable for words. . . .49

To fully appreciate how conservative the response of the NAACP was, one need only compare the Crisis editorial with that of the Chattanooga News:

. . . and now we see where blood has been shed in a “Communist riot” at Dadeville. One negro has been killed, two white men and five negroes wounded.

Five negroes have been “sent out after stovewood,” and have not returned. The inference is sinister.

Negroes gathered at a lonely cabin in the woods and began “demonstrating,” and speaking in favor of the release of the negroes at Scottsboro. . . .

The trouble is said to have started when the sheriff sought to disarm a negro sentry guarding the cabin. Why should the sentry have been on guard? Speech is free in America, and the negroes were entirely within their rights in meeting and protesting against the execution of the negroes at Scottsboro. The mere fact that they were protesting does not make them Communists, although a negro Communist from Chattanooga is said to have been the leader.

The entire affair calls for an investigation; especially the fate of the negroes who were “sent out for stovewood.”50

A month after Camp Hill the intimidation campaign against radicals in the South was in full swing, as shown in this article from the August 16, 1931, Huntsville (Alabama) Times:

Klan Marches

Several hundred members of the Ku Klux Klan marched through the downtown district [of Huntsville, Alabama] last night, and out into the thickly settled negro suburbs, in protest against the alleged spread of Communism in Huntsville.

. . . The Klansmen had the official sanction of the city government to march, since a traffic policeman led the way and halted traffic at each corner. . . .

One prominent Klansman told The Dally Times reporter that the organization had gone on record . . . against Communism, and that more drastic steps will be taken should the order continue to spread locally, as reputed among negroes.

That same month another Negro leader denounced Communists as the cause of unrest in the South:

Negro Bishop Regrets Unrest

Deplores Spread of Communism Among Race

Preaching racial integrity to preserve the negro, Bishop Socrates A. E. O’Neil, colored educator, is in Montgomery to combat communism and factors disturbing the relationships of whites and blacks. Bishop O’Neil’s work has the endorsement of national officials and governors. He insists that the white man is the Negro’s best friend in the south and will help more readily than the northerner.

Bishop O’Neil is an idealist of the late Booker T. Washington. In his work he denounces communism, interbreeding and vigorously opposes Oscar De Priest, negro congressman, and Abbott, the Negro educator, whom he blames for the unrest. “Stop them, stop the reds, stop miscegenation and lynching will stop.” Bishop O’Neil asserts. . . . He is an author and lecturer. . . .51

But despite the “Southern Terror”52 of the white racists and their shameless use of Uncle Toms like Bishop O’Neil, the ILD issued membership cards in Alabama and collected dues (two to twenty cents, depending on the members’ ability to pay).53 The point is not that few joined the ILD, but that any dared join at all. Their objective, after all, according to antagonistic reviewers, was almost too sinister to contemplate:

The red hordes of Communism that have swarmed into Alabama since. . . Paint Rock [where the Scottsboro boys were removed from the train] are intent on a much greater crime than any that might have been committed in the black gondola [open railroad car]. They would ravish the laws and social standards that condone racial discrimination, and bury them in the blackened ruins of revolution.54

There was increased Party activity in the South, but it never equaled that attained elsewhere in the nation with its countless Scottsboro rallies and even a Scottsboro March on Washington. Admittedly, on November 6, 1931, a Tampa, Florida, Scottsboro protest attracted 3,000 and on May Day, 1934, a downtown Birmingham park became a battleground between police and 5,000 radicals.55 These were exceptions; most of the Scottsboro rallies in the South were much smaller. But to those who were angered by the Alabama injustice and inspired by the Scottsboro struggle, the militant campaign evoked hope. As a Southern Negro miner declared: “I always wanted freedom. . . . All of us Negro miners wanted freedom, but we figured we could never get it. When we heard of Scottsboro, that meant freedom. From then on we knew we could win.”56

Much is written and published today on the history of the Negro in America, but all too often the authors display a narrow liberal bias. After reading some of these works one might conclude that the struggle against racism in America is confined to the deeds of the NAACP—the alleged vanguard organization in that struggle. What must yet be written, difficult though it may be in a nation whose creed is anti-Communism, is a full account of the role of radical movements and individuals in the anti-racist struggle. Also in order is an analysis of the basic conservatism of groups like the NAACP when challenged by the Jeft,57 as well as the reactionary role of some prominent Negro individuals in obstructing protest. Until such history is written, many people will continue to believe that the struggle for freedom in America was restricted to legal briefs, pnivate telephone calls, and secret deals. Admittedly, such quiet exchange by “respectable” politicians and attorneys are important, but it is mass confrontations and militant struggles that are decisive in advancing the cause of Negro freedom. The anti-racist vanguard in the South during the early 1930s was not the NAACP—it was the radicals under the red banner of the International Labor Defense.

University of Edinburgh

Edinburgh, Scotland

Notes

1 Gilbert Osofsky, The Burden of Race: A Documentary History of Negro-White Relations in America (New York, 1967), p. 359.

2 Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge, 1969).

3 Ibid., pp. 7-8. Cold weather and a contingent of national guardsmen aided in the persuasion. Indeed, the headline of one newspaper was “Cold Wave Prevents Lynching” (Pittsburgh Courier, April 4, 1931).

4 Although the prosecution merely asked for a verdict of life imprisonment in the case of the ninth, Roy Wright, whose age was either twelve, thirteen, or fourteen, a majority of jurors were unyielding in their demand for the death penalty. This resulted in a mistrial. (Carter, ibid., p. 48, states that Wright was then thirteen. The New York Times and most of the defense propaganda—including speeches by his mother—maintained that he was fourteen. When the State of Alabama released Roy Wright in 1937, it alleged that he had been only twelve at the time of the “rapes.” New York Times, July 24, 1937.

5 Hugh T. Murray., Jr., “The NAACP versus the Communist Party: The Scottsboro Rape Case, 1931-1932,” Phylon, XXVIII (Fall. 1967), 282.

6 William A. Nolan, Communism Versus the Negro (Chicago, 1951), p. 78.

7 Henry Lee Moon, Balance of Power: The Negro Vote (Garden City, 1948), p. 124.

8 Wilson Record, The Negro and the Communist Party (Chapel Hill, 1951), p. 86.

9 Nolan. op. cit., p. 80.

10 New York Daily Worker, May 14, 1931. A more critical account of these neighborhood committees which found them ineffective and limited to Party members and sympathizers can be found in the ultra-left New York Workers Age, May 1, 1933, and in the Militant, newspaper of the American Trotstyists, September 19, September 26, October 17, 31, 1931; March 19, 1932; February 4, 1933.

11 James W. Ford, The Negro and the Democratic Front (New York, 1938), p. 37.

12 Henry Winston, Life Begins With Freedom (New York, 1937), pp. 25-27.

13 Earl Browder, Communism in the United States (New York, 1935), pp. 25-27.

14 New York Daily Worker, July 5, 1931. Indeed, in three successive issues of Labor Defender, magazine of the ILD, there were articles on the Scottsboro case by Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos and Maxim Gorki (June, July, August, 1931.

15 New York Daily Worker, July 9, 1931; May 5, 26, 1934.

16 Daniel Guerin, Negroes on the March: A Frenchman’s Report on the American Negro Struggle, tr. and ed. by Duncan Furguson (Paris, 1951), p. 126.

17 Walter White, How Far the Promised Land? (New York, 1955), p. 215.

18 Lawrence D. Reddick, “What Does the Younger Negro Think?,” Opportunity, XI (October, 1933), 312.

19 Roger N. Baldwin, “Negro Rights and the Class Struggle,” Opportunity, (September, 1934), 265.

20 Theodore G. Miles, review of The History of Alpha Phi Alpha: A Development in College Life, by Charles H. Wesley, in Journal of Negro History, XXXIX (April, 1954), 153.

21 New York Daily Worker, December 13, 1933.

22 “Negro Editors on Communism: A Symposium of the American Negro Press, Crisis, XXXIX (April, 1932), 118.

23 Ibid., XXXIX (May, 1932), 156.

24 Benjamin J. Davis, “Why I Am a Communist,” Phylon, VIII (Second Quarter, 1947), 109.

25 Asbury Smith, “What Can the Negro Expect from Communism?” Opportunity, XI (June, 1933), 211.

26 Joseph William Nicholson and Benjamin Elija Mays, The Negro’s Church (New York, 1933), pp. 5, 9.

27 Record, op. cit. pp. 38, 82. Ralph Lord Roy, “Communism and the Churches,” Communism in American Life, ed. by Clinton Rossiter (New York, 1960), pp. 46-47.

28 Roy, op. cit., pp. 50-52.

29 Harold F. Gosnell, Negro Politicians: The Rise of Negro Politics in Chicago (Chicago, 1935), p. 328.

30 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Marching Blacks: An Interpretive History of the Rise of the Black Common Man (New York, 1945), p. 69.

31 Roy, op. cit., p. 53.

32 Earl Browder, What Is Communism? (New York, 1936), p. 194.

33 Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander (New York, 1956), pp. 60-61.

34 Nancy Cunard, ed., Negro Anthology, 1931-1933 (London, 1934), p. 142.

35 Ibid., p. 141.

36 Jackson Country Progressive Age (Scottsboro, Alabama) December 31, 1931. The other Scottsboro newspaper had previously denounced Contempo and reprinted one of its articles under the heading: “Communists Start Newspapers To Carry Propaganda . . . First Issue Devoted to Amazing and Malicious Deception of Facts in Scottsboro Case,” (Jackson County Sentinel, July 9, 1931).

37 Cunard, op. cit., p. 142.

38 Langston Hughes, “Cowards from the Colleges,” Crisis, VIII (August, 1934), 227. A professor and a student from a white college, Birmingham Southern, did address a Scottsboro protest rally. For a discussion of the consequences, see Carter, op. cit., pp. 254-58.

39 Miles Crenshaw and Kenneth A. Miller, Scottsboro: The Firebrand of Communism (Montgomery, Alabama, 1936), p. 292.

40 Carter, op. cit. , pp. 127,153.

41 New York Daily Worker, May 30, 1931.

42 Chattanooga Times, April 1, 2, 3, 4, 19, 1931.

43 New York Daily Worker, June 2, 1931.

44 Edmund Wilson, “The Freight-Car Case,” New Republic, LXVII (August 26, 1931), 42.

45 New York Daily Worker, June 9, 1931.

46 New York Times, May 24, 1931.

47 Carter, op. cit., pp. 128-29. He described the incident in more detail on pp. 123-28.

48 The views of the ILD’s secretary, J. Louis Engdahl, can be found in the New York Times, July 18, 1931. Roger Baldwin of the ACLU spoke about the Camp Hill Incident in the New York Times, July 19, 1931. The Urban League magazine, Opportunity, also discussed the incident in “Communism and the Negro Tenant Farmer” (IX, 36).

49 W. E. B. Du Bois, “Postscript,” Crisis, XXXVIII (September 1931), 313. [It is to be noted that while the NAACP persisted in its anti-communism, W. E. B. Du Bois changed his position. In subsequent years he fought the conservative leadership of the NAACP, ultimately leaving the organization and taking his stand among the most radical leaders of his people. After working with the Communist Party for a long time he finally joined it in 1960 at the age of 92 and died a Communist.—Eds.]

50 Chattanooga News, July 18, 1931. For another example of the conservative nature of the NAACP it is interesting to read in the white supremacist Jackson County Sentinel a reprint of an editorial supporting contentions of the NAACP’s Walter White (Jackson County Sentinal , December 31, 1931).

51 Alabama Journal (Montgomery), August 13, 1931.

52 See Louise Thompson, “Southern Terror,” Crisis, XLI (November, 1934), 329.

53 Crenshaw and Miller, op. cit., p. 296.

54 Ibid., p. 290.

55 New York Daily Worker, November 6, 1931; may 4, 1934. For a fuller discussion of similar activities see John Williams, “Struggles of the Thirties in the South,” in The Negro in Depression and war: Prelude to Revolution, 1930-1945, ed. By Bernard Sternsher (Chicago, 1969), pp. 166--178.

56 Nat Ross, “Some Problems of the Class Struggle in the South,” Communist, XIV (January, 1935), 66-67.

57 A tentative beginning of a reappraisal can be seen in August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, “The First Freedom Ride,” Phylon, XXX (Fall, 1969), 213-22.

Posted April 15, 2007